News feed

“Work that fits somewhere in between design and art,” is how the designer Jonathan Ben-Tovim describes the sea of design works sprawled out before him. Included amongst those are Ben-Tovim’s own, as well as those of his co-curators, Michael Gittings and Makiko Ryujin, who together enlisted seven other designers to exhibit their work as part of a group show staged as part of Melbourne Design Week that surveyed works that, while they perhaps did not have a clear commercial outcome, were concerned with far more interesting matters.

Many of the works exhibited in Artefacts further conflated the already hazy distinction between objects of art and those of design; some existed as material explorations, or were driven by an interest in narrative beyond mere utility. That each participant made their work by hand resulted in a sense of cohesion beyond what was evident visually, though it was possible to trace through lines between many of the works being exhibited.

“The theme of ‘artefacts’… was partly about this idea of pieces that could come from any period of time,” explains Ben-Tovim. “The idea that, if you’re creating design, ultimately the best outcome is to create an artefact that people might want to hold onto and say something about the time you work in. We wanted to choose works that fit into that.”

Driven by a desire to carve out a space for those whose works do not so readily fit into either a gallery space or design showroom, the three co-curators – who also share a studio in Fawkner in Melbourne’s north – engaged their contemporaries in a dialogue that they hope will further conversations of what design is and what it can be.

Herewith, each of the designers-come-curators discusses their own work exhibited as part of Artefacts.

Bringing Sexy Back

Where his day job sees Ben-Tovim concern himself with conventionally desirable lighting and furniture products for use in interiors, the designer harbours a side practice driven by unearthing more interesting applications for materials that are no longer wanted. All of which is not to say that Ben-Tovim is proposing sustainability solutions hinging around upcycling; instead, his interest lies in transforming materials in a manner that subverts our expectations of them entirely. In Crash, a collection of oily black bowls almost viscous in appearance and three dynamic lights, Ben-Tovim re-appropriates sections of car wreckage sourced from the panel beating workshops surrounding the designers’ Fawkner studio.

“[There was] this idea of taking things that are unwanted or discarded and used for different purposes and seeing if I can take the language of whatever that is and flip it [to] make it something desirable and give it a completely different meaning,” Ben-Tovim says of the rationale behind the objects in Crash, a collection named for the 1996 David Cronenberg film of the same name exploring the erotic phenomenon experience by those who derive pleasure from automobile accidents. Abstracted from their origins as scrap metal, each piece is underscored by an element of chance, its shape and utility largely contingent on the accident that birthed it. To create the pieces, Ben-Tovim sectioned out what he describes as the most interesting parts of the panels, using an angle grinder, before stripping back the surface using sandblasting processes until returning the material to a raw state. An application of automotive paint hints at their original use, creating pieces that manage somehow to be both humorous and macabre. A glossy finish also helps to make something once considered worthless strangely desirable. It’s no small feat that Ben-Tovim has, in his words, “made them sexy objects again.

“I’ve got plenty of material to work within the area, so I will probably try and experiment some more. It’s an homage to the local area”, he adds, laughing.

Making Weaves

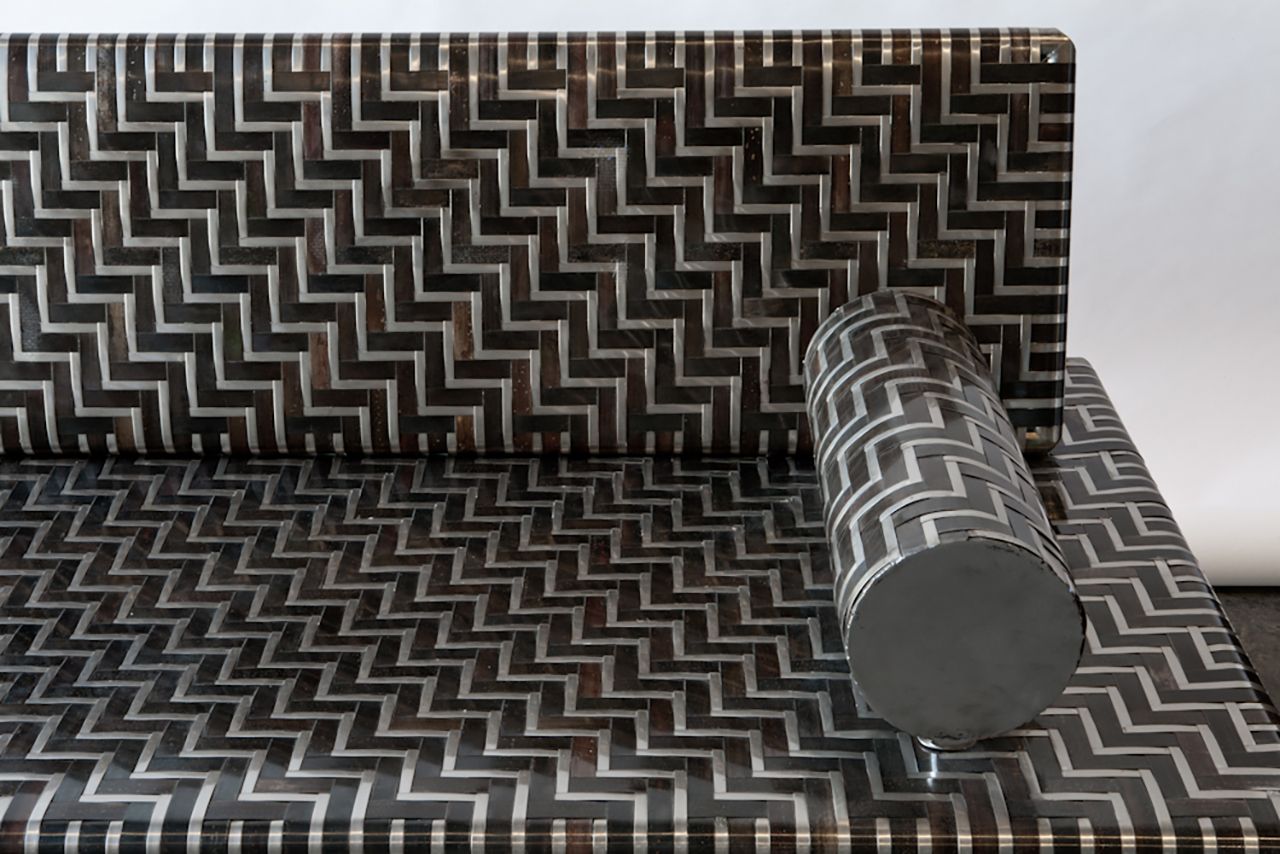

Michael Gittings has what he describes as “quite a long history in the construction industry”. The designer spent seven years plying his trade as a roofer before pursuing furniture fabrication full-time last year. The move not only gave him a deep appreciation for metal fabrication and materiality, but an outsider’s perspective on his craft. Perhaps even more handily, he now has “fingers like leather” that allow him to explore the possibilities of his current preoccupation: a stainless-steel weave that can only be achieved through working with bare hands.

For Gittings, the process is a relatively new one. It’s also laborious. To create the Franz Chaise, Gittings attached strips of steel to a frame before weaving the strands onto its structure. The chaise itself is an understated homage to the work of Franz West, the late Austrian artist and designer who made a set of “extraordinary upholstered furniture”. It’s possible to trace the influence of West’s Divan (1991) and Chaise (1992) in the graphic, linear structure of Gittings’ work. To create a second piece, the S01 Screen, “the laws of physics” dictated that he weave a single panel of steel on the ground before folding it into shape over four laborious days. It’s certainly no small feat.

The most time-consuming process, however, lies in the staining of the stainless-steel to produce a darker finish using pre-mixed chemicals and heat treatments to achieve a patination. It’s one of many practices verging on mad science that are currently preoccupying the designer, who in the past has transformed copper into alien shapes using electroforming and electroplating processes. Perhaps the most surprising element of Gittings’ experimental process, and his disarming collection of furniture that straddles the divide between past, present and future? “It’s surprisingly soft!”

Shinki Inferno

After Makiko Ryujin has spent two weeks carefully turning wood on a lathe, transforming her raw material into beautiful bowls that are then left to dry for two weeks, she sets them on fire.

“It’s quite amazing, [what] happens,” says Ryujin. “Watching it change, and hearing the sound as it splits during the burning process.”

Ryujin, a wood-turner and photographer originally from the Gunma prefecture in Japan, uses green pin oak to craft her remarkable vessels. The wood lacks moisture retaining properties, meaning that it’s prone to warping within a matter of days through simple air drying. Some of the works have holes drilled into them before they are burned over a backyard bonfire; other vessels are used to contain a fire in their hollow, burning them from the inside out, charring the edges and further distorting their shapes while also investing a sense of the elemental into each work. They’re later treated with Carbothane to strengthen and seal the work, and to prevent ash from ending up everywhere.

“In Japan, we keep bowls on ornamental shrines that are used once a year in [religious ceremonies],” Ryujin says of the impetus for her Shinki (Burning Series) collection. “I imagined those bowls [that are] used in the ritual sense.” In Japanese, she explains, the character ‘Shin’ represents ‘God’ and ‘Ki’ translates as ‘vessel’. In each Shinki, there is a discernible tension between control and release evident in the contrasting treatment of the wood. “So much of [my] intention is to make a shape, but design can happen without intention too. This is a collection of design [objects] where I both had [and relinquished] control. It’s a mix of two elements of natural [processes] and intervention.”

Melbourne-based for the last 18 years, Ryujin has worked mainly with wood for the past two years, though comes from a photography background – something she still practices today. The unnerving pursuit of perfection demanded by photography lead her to wood-turning, and eventually, to release.

Tile and cover image: Supplied