News feed

In Hermès at Work, a new exhibition open now at Melbourne Town Hall, every handmade objet tells a story – regardless of the state of completion you find it in.

In one corner is the story told by an exquisite Le bracelet Galop d’Hermès, suspended as though it were floating in a glass vitrine. On the horse head and chain links of the bracelet are six thousand diamonds, each no larger than the head of a pin, which can take up to three months to embed. If the man who made it invites you to look at a cross section through the lens a microscope, accept his invitation: it is incroyable.

In another corner is the story of the making of one of the house’s iconic Kelly handbags, the rigid folds of which can take a week to bend to submission. A week of persuasion and then, finally, it yields – all that work to give the impression of effortless style.

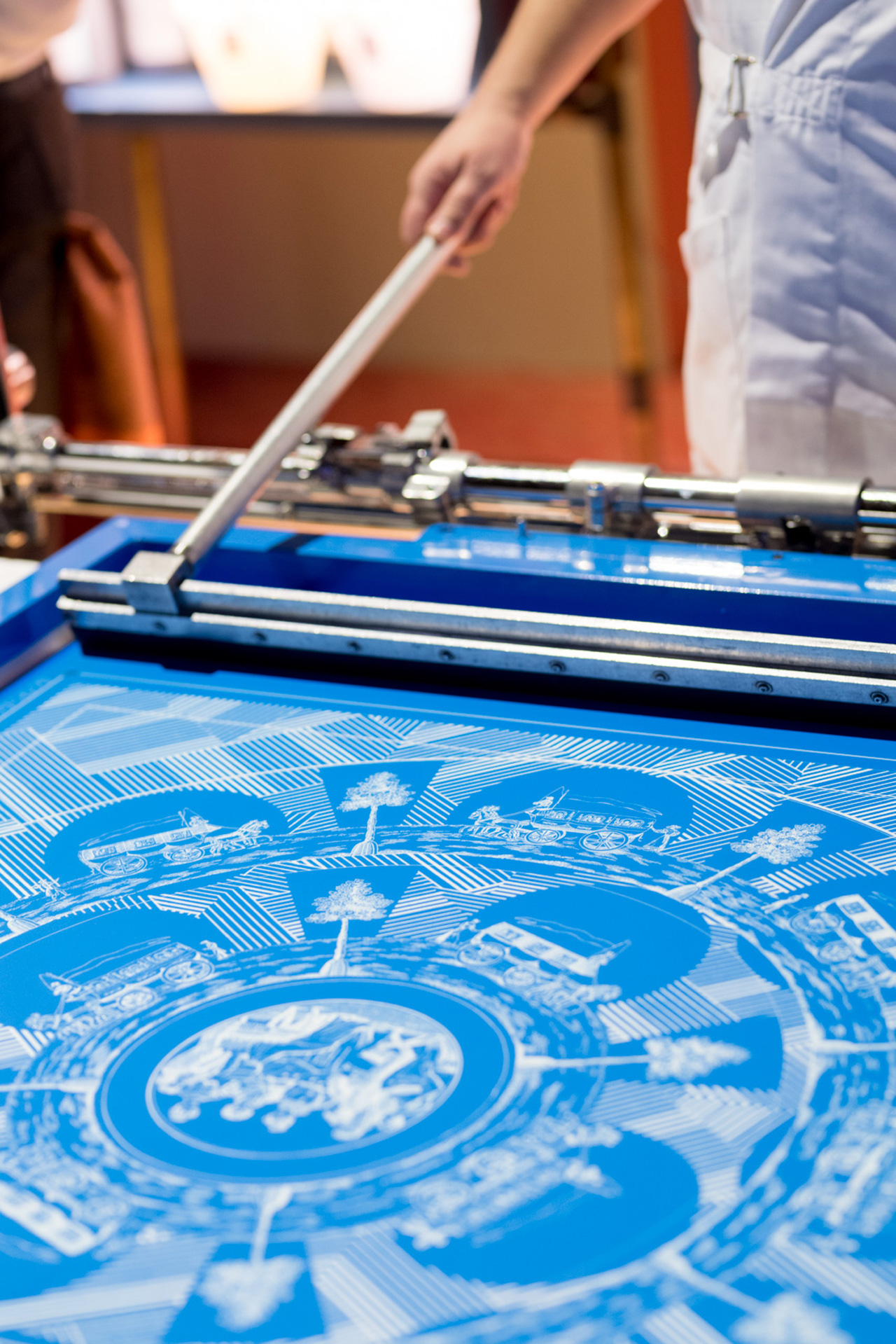

In another still there are the many stories told by Christian, a glove maker from Saint-Julien in the south of France, who for 30 years has used five-fingered folds of butter soft lambskin to craft tales that can vary in length from five to nine hours – depending, of course, on the length at which you prefer your gloves. For 28 of those years, Christian has been proud to know Kamel Hamadou, a colleague at Hermès and an expert in silk screen printing who hails from Lyon and who is stationed out of sight from the glove maker across the room and behind a number of brightly coloured partitions.

Both men have devoted three decades of their life’s work to the house of Hermès, though to hear them tell it, there is nothing about this that is even close to a semblance of work as you or I may know it. Through Hermès at Work, a travelling exhibition that has taken Hamadou in particular to some 40 countries since it began in 2011, both men have had the chance to meet and hear the stories of their contemporaries: the craftsmen and women stationed throughout France whose expertise in their respective fields gives birth to a brand of luxury that is unique to Hermès. For Christian and Kamel, and the seven other artisans stationed throughout the palatial Town Hall, the chance to embed here for two weeks and share their passion not only with audiences but with each other is not work. It’s magical.

“What is exciting about this exhibition,” says Guillaume de Seynes, Executive Vice-President of Hermès International, “is that it is always slightly different because of the location but it has been successful all around the world. Why? Because I think that there is a universal curiosity [as to] what is behind these products. What is the know-how? How can we better understand these iconic products, the bags and scarves?”

Though he is a sixth-generation descendant of the Hermès family members that founded their eponymous house in the 19th century, de Seynes is quick to admit that he would not have been permitted to join the company as an artisan, but not for the want of trying. He once spent three days to craft an agenda cover from leather in one of Hermès leather workshops that employ some three thousand – a task that would ordinarily take an experienced artisan two hours to complete. Though the gesture was admittedly a tokenistic one – the result was not fit for sale, he recalls laughing – it instilled within him a respect for the craft and creativity that are the cornerstone tenets of the house and those who work under its name. “I don’t have l’intelligence de la main [the cleverness of the hand]”, he admits. But it is not just a deft hand that is prized above most when the house looks to enlist the next generation of talent. According to Hamadou, big heart is a quality desired as much as technical finesse. Pride in one’s work and a profound respect for the work of one’s contemporaries is paramount.

“Hermès is about craftsmanship and excellency, and it has been the pillar of this company since my ancestors [founded the house] in 1837,” says de Seynes, whose arrival in Australia this week necessitated that he decline an invitation to join the most prominent members of the fashion industry in an audience with French President Emmanuel Macron at the Élysée Palace. “Hermès at Work started in 2011; every year we have a theme for Hermès [and] that year was ‘contemporary craftsman’. Those two words are of equal importance… because what we want to show and explain is that [this] is a living reality, it’s an everyday reality, this craftsmanship and know-how.”

The goal then with Hermès at Work for the family-owned company is not purely profit driven – admission is free – but undertaken with a generosity of spirit that borders on evangelical. Hermès at Work is as much for customers both established and prospective as it is those for whom simple ownership is beyond reach, says de Seynes. Hermès at Work asks nothing of you other than you listen to its stories (each artisan is accompanied by a translator), to witness the savoir-faire of a process that can last anywhere from two hours to two years – the finished product of which are luxury goods nonpareil, made using techniques that have either remained unchanged for 180 years or those that have been implemented as recently as five years ago.

“It’s [about] understanding who we are in-depth,” says de Seynes. “Who Hermès is.”

Before he began working in one of the eight Hermès workshops stationed in Lyon in 1986, Hamadou used to work for Kodak. A one-month contract cleaning what were then the wooden frames of the silkscreen printing press (today they are made of steel) turned into a three year printing stewardship that he says feels as though it were embarked upon only yesterday. Today, he says, his métier is that of a storyteller whose pleasure in one’s work is derived from seeing the same reaction that he witnesses in audiences around the world: their eyes engorged and illuminated in amazement at seeing first hand the process of creation from ideation to completion.

A dialogue between creativity and craftsmanship is central to the heart of Hermès. The dialectic is embodied most succinctly in the theme of ‘Everything changes, nothing changes’, a subject on which de Seynes delivered a sold-out keynote speech on the evening of the opening day of Hermès at Work. The epigram speaks to balance between contemporaneity and artisanship, with a healthy dose of ambition fuelling both ends of the spectrum. Its roots are traceable as much in the present moment as they are in the 1920s, when de Seynes’s great-grandfather, Émile Hermès, made what was then a startlingly new proposition to pivot away from the house’s equestrian roots and focus its attention toward a class of consumers who were increasingly fascinated by the concept of travel-as-leisure, as mobilized by the advent of motoring. The genius of his great-grandfather Émile, de Seynes says, was to use the same saddling know-how to craft new leather goods without sacrificing the distinctive stitching techniques, thus birthing what he calls the ‘Hermès style.’

“He [made] this move by keeping the craftsmanship and the know-how about what we call ‘saddle stitching’ but proposing new items [utilizing technologies] such as the zipper, which was very modern at the time and proposing travelling bags, trunks and accessories,” says de Seynes. “This has been something that we are constantly trying to follow: this duality between roots and [contemporaneity].”

The zipper, as it turns out, was just the start. Today, the house prides itself on its pioneering approach to conflating time-honoured artisanal practices with new technologies on the proviso that doing so enhances the hand of the craftsperson without diminishing their role in the resulting product. In Hermès at Work, Hamadou and his colleague Frederique are reproducing for audiences the first design ever produced for silkscreen printed silk scarves by Hermès in 1937. Where once wooden stamps were used to apply ink to silk, today digital screens are engraved with the impossibly detailed renderings that are contributed by both the 40 artists that Hermès keeps in-house and external contributors alike (internal artists are kept on a freelance retainer to allow them the creative freedom to take on other projects). The technology to create digital silkscreen printing layers has only been around for five years, and the practitioner exhibiting as part of Hermès at Work, Nathalie, a silk engraver from a town outside Lyon, says that she much prefers this new digital method to the laborious analogue technique that predated it. One design she applies her hand to, a rendering of a samurai featuring infinitesimally small details, requires that she carve out those miniscule features on 47 different screens. The work is as mentally strenuous as it is physically taxing, a reality that de Seynes acknowledges must also change with the aid of technology. “We are adapting the process especially for ergonomic reasons,” he says. “We are not technology averse at all, but it needs to offer the same quality at the end and magnify the know-how and not replace the hand. The role of [Nathalie] is still the same; the tool has changed.”

One arena in which this has not changed is leather. It’s no accident that Hermès at Work both opens and concludes (provided you walk through the exhibition in an anti-clockwise fashion) with three open-plan booths devoted to the art of producing the company’s world renowned leather goods. Hermès was founded as harness maker; it wasn’t until much later in the 1880s that saddles were added into the equation. Though the house no longer makes harnesses, the brand’s leather goods are made in the same Parisian workshops they were more than 180 years ago. It’s from there that the genius of Èmilie Hermès is still readily discerned today. As a product category, the original métier of the house of Hermès accounts for 50 per cent of the group’s sales; its turnover in 2017 attained €2,800 million, an increase of almost ten per cent at constant exchange rates. The sector’s cultural cachet is greater still to both the brand and its customers, recurring and potential alike, as well as its employees who still work by the guideline of ‘one craftsperson per bag’. Speaking with them, it becomes evident that it’s to this category that Hermès owes both its past and a great deal of its future – everything changes, nothing changes, as it were. The challenge the brand faces now, de Seynes concedes, is to continue channeling that spirit; to maintain an equilibrium between an integrity of product fuelled by the extraordinary know-how of its craftspeople and the technology at their disposal, while never losing sight of the entrepreneurial spirit from which the house was borne. “The rule of the hand can’t be replaced,” he says.

For his part, Hamadou has never forgotten what first cemented his decades-long relationship with the house. It was the silk, pure and simple, arriving as it does in cocoon form from Brazil before it is transformed into something entirely otherworldly by the hands of the artisan. He fell in love with it, he says. Some people fall in love with cities, or with people, but for Hamadou, it is silk and the two-year process of making one of the legendary Hermès carré scarves to which he returns. In the years he has worked at Hermès across its eight manufacturing outposts in Lyon, he has amassed a collection of over 200 silk, cotton and cashmere ties. Though he is a lifelong employee, he says he is above all a fan – one who is simply in love.

On the day that we speak, Hamadou wears a tie in the signature Hermès orange, embroidered with endless cartoonish permutations of a koala bear in a deferential nod to the audience whose attention he will court. When his wife gave birth to their daughter 26 years ago, his first gift to the newborn was an Hermès carré, not in silk but in cotton. The gesture was an act of transference, the beginning of a new relationship that he says he struggles to understand himself; it’s just there within you, an innate connection to fabric felt as much in the hand of the artisan as the face of a newborn.

His voice turns whisper quiet as he tells the story, and for the first time in a long time, he doesn’t know what to do with his hands.

Hermès at Work will be presented at Melbourne Town Hall, from March 8 to 17, 2018. Admission is free between the hours of 11am to 7pm. More information is available here.

Tile and cover image: Courtesy of Hermès