News feed

Credit: Ralph Orlowski/Getty Images

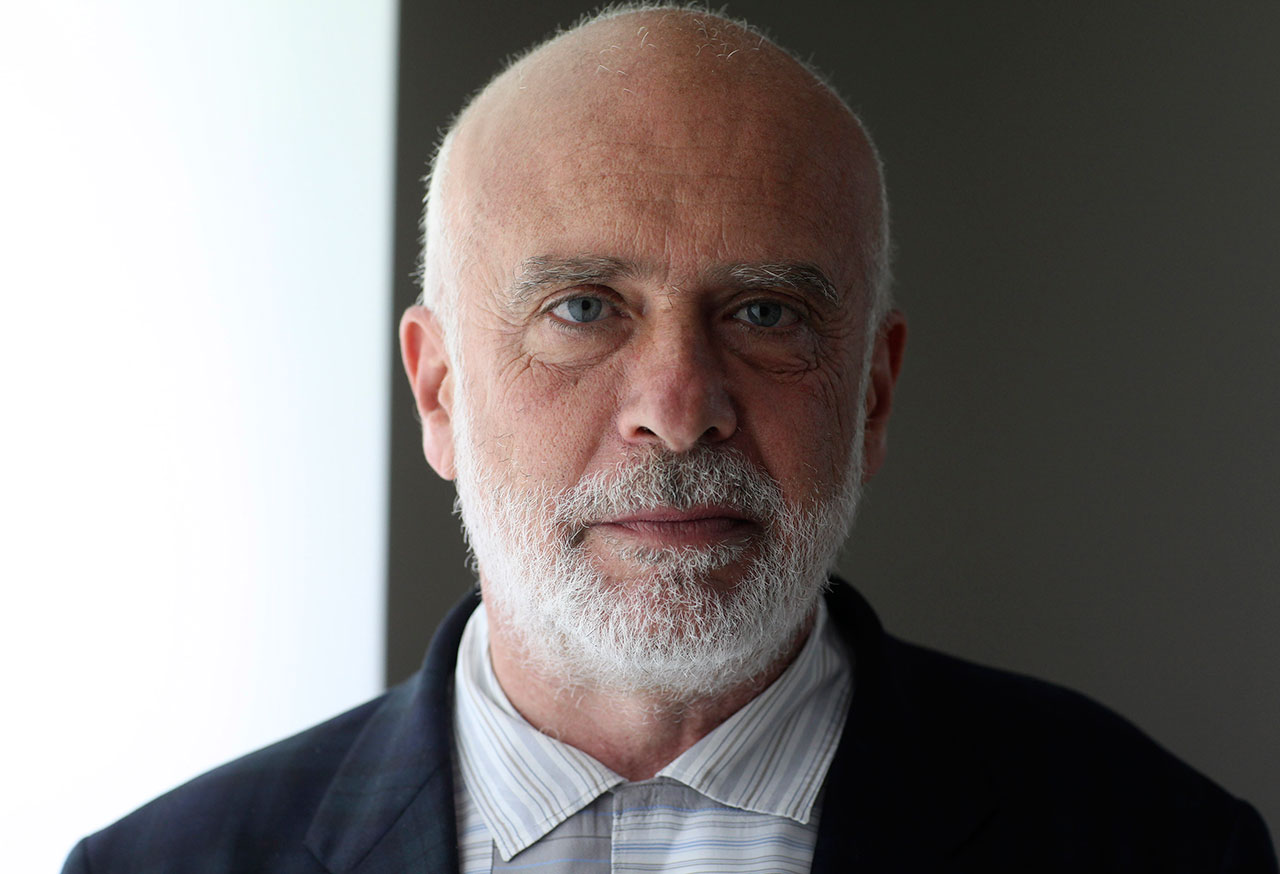

Despite having spent much of the last week building a universe, Francesco Clemente is cold.

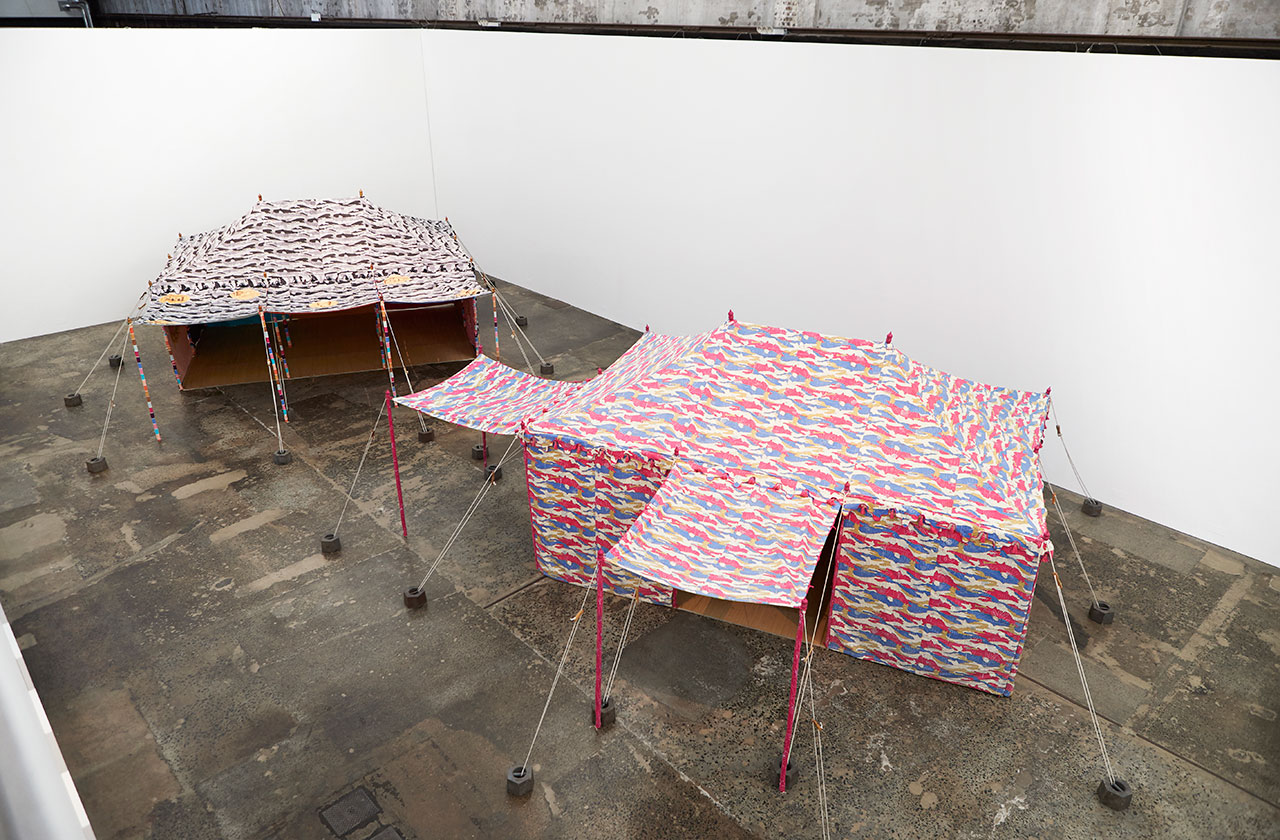

The Italian artist has been busy erecting the tents that when grouped together will come to form Encampment, an exhibition of his work on show now at the cavernous Sydney arts institution Carriageworks. Each tent in the series “is like entering a universe in itself”, according to Clemente, whose tents originally showed at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in the latter half of last year. Working in collaboration with a community of artisans in Rajasthan, India, over the last three years, Clemente has hand-painted vibrant and often ornate tempera frescoes inside each of the six tents depicting a variety of scenes from both his life, history and religious allegory in equal measure, each akin to its own little world set sprawling over 30,000 square feet.

“The installation is very elaborate,” says Clemente, as he moves outside and into the sunshine to discuss the construction of his miniature tent city, and the road that has lead him here. Warmed by the sun and an ample navy brocade scarf so large that that threatens to envelop him, he reflects on his first visit to Australia for the first major exhibition of his work after an acclaimed career spanning some 50 years.

“I did have a few moments with the wind and the scents,” Clemente recalls fondly. “With the eucalyptus, the tea trees, I love it. Australia is the land of scents.”

Below, the New York based artist speaks with GRAZIA about Encampment, his peripatetic life so far and, sure enough, his inevitable death.

Credit: Zan Wimberly

When did you begin work on the series of tents that comprise Encampment? “I’ve wanted to make tents for a long time, maybe from day one of my endeavour, but they finally came together in 2011. What you see in the exhibition has been made over the arc of four years. I’m based in New York but I spend a lot of time in India. The entire exhibition is made in India and New York, too. These are the two polarities.”

Why did you choose tents as the medium for your work? “It’s a way to smuggle painting into the picture. I’ve been called a nomadic artist over and over again so I thought I would take this definition literally. I asked myself, ‘What are the implements of a nomadic life?’ and the first thing that comes to mind is tents, and their vocabulary – the weights, the ropes, the walls, the ceiling. So [each tent is] like entering a universe in itself.”

Why do you think it is that you’ve been labelled a ‘nomadic artist’ over the course of your career? “Because I grew up in what I thought was a culturally bankrupt stage of European history and I decided to escape that by moving to India. I really wanted to enter geography to escape from history. I have lived a nomadic life between India, New York and Europe ever since. I first went to India in 1971, I lived in Chandigarh and then in Kashmir, in Old Delhi. I was just happy to be elsewhere; we are talking of a world that was not as colonised by capitalism as it is today and I felt very fortunate that I could step out of the capitalistic narrative and into other narratives. I also visited Afghanistan in those years; you could actually step out of the mainstream narrative and find yourself in other realities.”

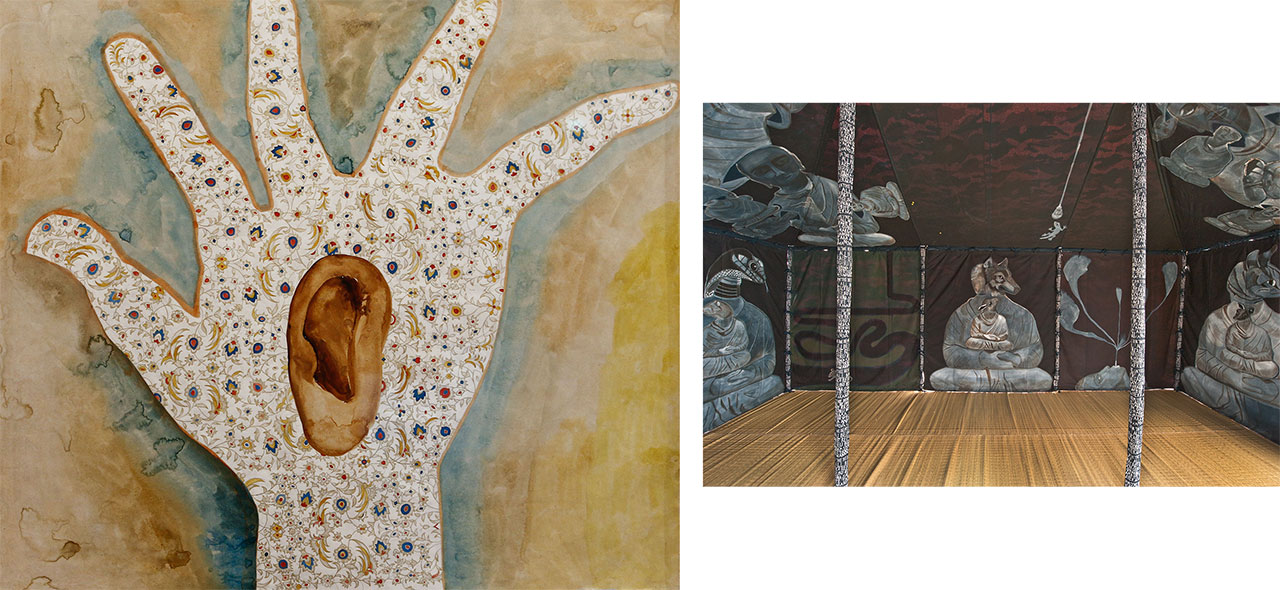

Credit: Zan Wimberly

At left, Francesco Clemente No mud, no lotus 5, 2013-2014, watercolour and miniature on handmade paper; Francesco Clemente, Taking refuge (interior view), 2013, tempera on cotton and mixed media

Credit: courtesy of the artist and Blain|Southern Gallery, Berlin

Before escaping to india, You grew up as a child in Naples, Italy. Was there ever a moment where you had an epiphany about wanting to live your life as an artist? “I always wanted to be an artist, but I always wanted to be an artist by default in the sense that I was an artist because I did not want to be any other thing. I did not want to be part of the dynamics of power and authority that I saw around me in Italy and the world at large. I’ve always been reluctant to embrace the narrative of power. I think now that my role as an artist is to offer an alternative narrative.

“I had a fantastically boring childhood. Boredom, however, is the mother of all creation.”

“I knew that I wanted to be an artist quite early but I found my voice quite late; it took me a long time. I found it in my mid-twenties but it took me ten years to figure out who I was. India definitely helped me find my voice, but it’s always one thing. What I did was to make hundreds and hundreds of drawings. I used to walk over a carpet of ink drawings daily – it was almost a ritual practice.”

Erecting a tent is often a laborious, methodical exercise. Can you describe the process of creating these tents? “I make all my works in collections and that way I imagine each collection to be more than its own. I begin by counting how many I want to make, and then I draw in a very primitive, concise way the images that will come together. Then I adopt a medium – in this case the tent is the medium and the format – and then when all of this is set, I paint. The fact that I have this order allows a lot of freedom.”

Credit: Zan Wimberly

Was it a very collaborative process, or is the process of painting the interiors a very solitary one? “The making of the tent is very collaborative because so many crafts enter into play – embroidery, silkscreen, the carving of wood blocks, the printing of the blocks, the stitching of the tent. All that you may call collaborative, but the painting I do by myself.

“To be an artist is wonderful because you are always alone but to have company is even better.”

Each of the tents tells a different story. Museum tent in particular seems more concerned with your own life, your career and your mortality than others, lined as it is with arresting self-portraits featuring skulls or a noose. The accompanying statement suggests that “anything found in a Museum is dead to life.” having twice exhibited these works in an institutional context, would you consider them now to be dead or alive? [Laughs] “There would not be any art without mortality. The origin of art is really the acknowledgement of death. I’m only asking questions. We test the boundaries of everything – this is one of the things that one does as an artist, to test your boundaries, the boundaries of your audience and the boundaries of art making. Obviously I hope to bring life into the realm of the dead [laughs].”

Do you fear death? “Fear of death has definitely been my motive to become an artist. One hundred per cent. Do I fear death now? No.”

Why not? “Because I have understood that what dies is only a small part of me. Not the whole thing.”

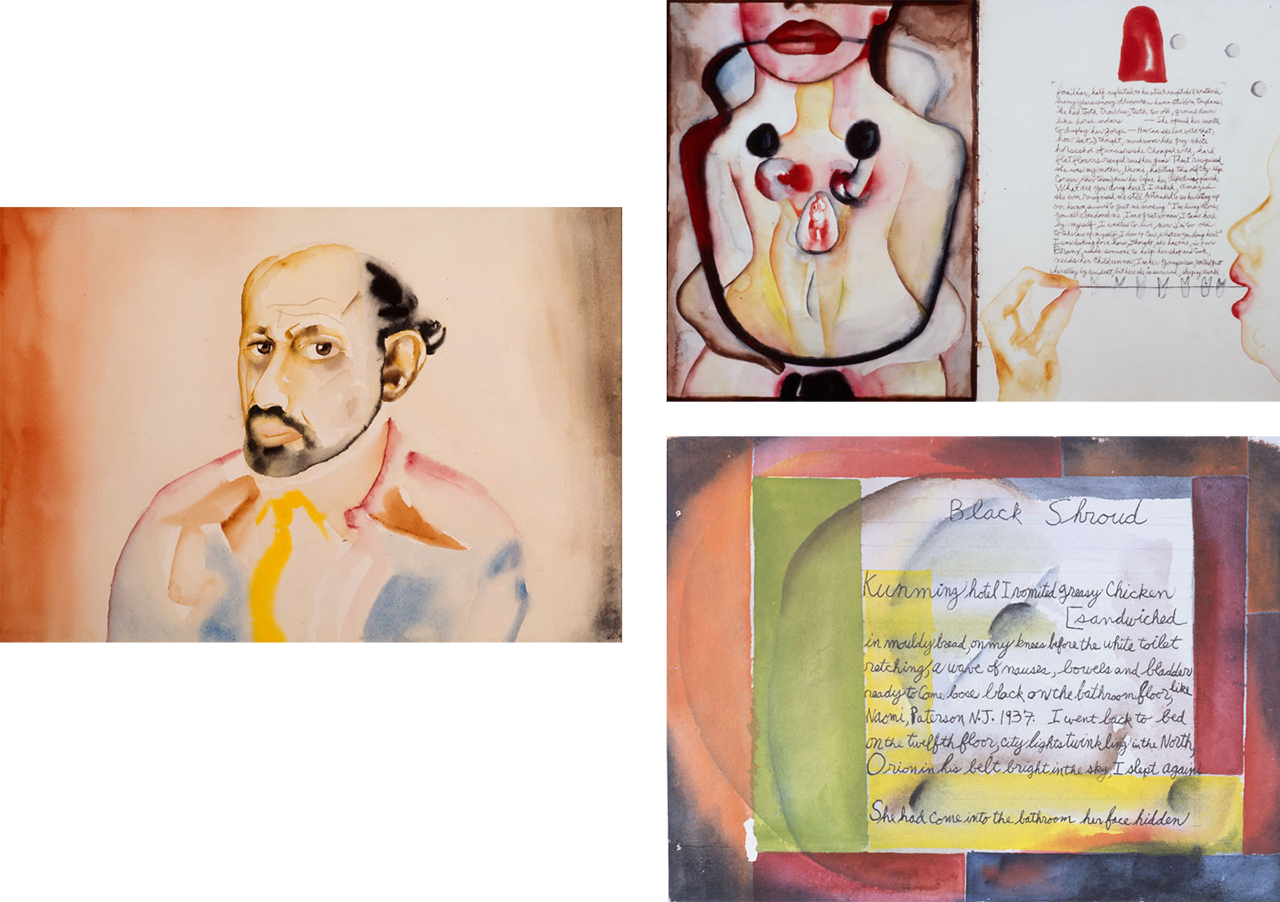

Credit: Zan Wimberly

At left, Francesco Clemente, Angels’ tent (detail), 2013; Francesco Clemente, Moon, 2014, mixed media

Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Mary Boone Gallery, New York

Some of the tents feature religious iconography – Byzantine devils and angels who’ve fallen asleep because “indifference wears one out more than hate”. Do you consider yourself to be a spiritual person? “What is ‘spiritual’? Spiritual means to not have any fantasies. In this way, I am a very spiritual person. I have no fantasies. We should all take responsibilities [for our actions].”

Exhibited alongside the tents are four shrine-like sculptures: earth, moon, sun and hunger. The tents almost take on the quality of places of worship. Is there also an element of piety here? “That is definitely the correct perception. The question now is, ‘the worship of what?’ All of the work mimic the dynamics of a religious practice, except it is an open field. It’s not confined to a particular view.”

The 19 paintings from a series titled No mud, no lotus that line one of the walls are quite erotic in nature. Do eroticism and spirituality play hand-in-hand? “Absolutely. This doesn’t come from me, however. There are many contemporary traditions that use the erotic life as a metaphor of spiritual life in the sense that both are the only parts of life that never end.

“It’s story telling that opens a door hopefully. One story leads to another. I’m not really sure of what the next story will be but I’m open to it.”

Credit: Zan Wimberly

You still lead a very itinerant life now, being based between New york and india and travelling abroad for work – you must be constantly in transit. Do you feel attached to any one place? “The goal of my work and my life is to stay in a fluid state – not to solidify anything. The way I present my images is very fluid and not mean to be static or dogmatic. That’s all it is – to keep oneself free of unnecessary fantasies and to keep yourself in a state of movement. I came to New York in 1981 from India and I went to an exhibition very unexpectedly and ended up staying. I stayed for the community. All of a sudden I had friends and had been quite solitary until then. At that particular time, New York had a very vibrant community of artists, dancers, musicians, painters all from different sources. There was hip-hop coming in, the New Wave of film, the European painters, the avant-garde dancers. It was very special.”

Does New York have that same sense of community for you? “Less so. At that time, New York was a bankrupt city that was open to the young and the poor. Now it is a prosperous city that is hard to live in for a young person with ideas. Today there is still a strong community.

On moving to New York, you collaborated with artists like Allen Ginsberg, Andy Warhol, and Jean Michel Basquiat. Have you ever considered another artist to be a mentor of yours – someone who has shaped you both personally and professionally? “I had a mentor, Alighiero Boetti, he was an artist from the Arte Povera generation but he was marginal to the main concerns of that movement. His work lead him to Afghanistan and he’s the artist from the generation before mine who opened the door for me. He died at 54. He was a difficult person, but a great friend and taught me how to think as an artist, even if his work on the surface is very different and far from mine.”

At left, Allen Ginsberg 1982-1987 Watercolour on paper; top right, Allen Ginsberg and Francesco Clemente’s White Shroud 1983, Ink, pencil, watercolour on paper and below that, Allen Ginsberg and Francesco Clemente’s Black Shroud 1984, Ink, pencil, watercolour on paper

Credit: Courtesy of the artist

Do you see yourself today as having a similar relationship with another artist? “One of my favourite artists right now grew up basically hanging [around] my house and studio. He was part of a collective in New York that I like very much but now he’s on his own. He was one of the founders of The Bruce High Quality Foundation and now he’s doing his own work. G.T. Pellizzi is his name. He also grew up between cultures.”

What is your studio environment like now? Do you still enjoy the company of others in that environment? “I have studio downtown and a second one in Green Point. I’m nomadic even in New York – I cross the bridge back and forth. My operation is tiny, a studio manager, a once-weekly painting assistant and an archivist. It’s nice to have company but it’s also nice to close the door and be alone. I’m a father of four, a grandfather of two – all of those things. We are a family without glue.”

What would you like your legacy to be? After the tents are packed down and put away long after you’re gone, how would you like to be remembered? “Remember, the sage leaves no trace. The wise man leaves nothing.”

Francesco Clemente: Encampment is open now until October 9 as part of the Schwartz Carriageworks series of major international visual arts projects. Entry is free from 10am until 6pm daily.

Tile image: Ralph Orlowski/Getty Images

Cover image: Francesco Clemente, Museum tent (interior view), 2013, tempera on cotton and mixed media, courtesy of the artist and Blain|Southern Gallery, Berlin