News feed

There is no shortage of discoveries to be made about the Sydney-born artist John Russell but my favourite, perhaps, is this.

When Russell, who was born in Darlinghurst in 1858, was 23-years old, he did as many young Australians do and decamped to London. There, he enrolled at the Slade School for Fine Arts where, for 18 months, he trained under the French realist Alphonse Legros and honed his skills as a classical portraitist with a deft hand at drawing from memory. By all accounts Russell was well-liked, adept at cultivating meaningful friendships, and was particularly outdoorsy (when he later moved to Paris, he would row on the Seine and started a boxing club, much to the bemusement of his French contemporaries) – a typical Australian living abroad in London, the very image of a scene as much at home in the late 19th century as the 21st. It’s some small comfort to know that little has changed between now and then. When Russell returned to Sydney in June 1882 as an ambitious 24-year-old student, he did so with all the worldly bravado and self-assuredness of any Australian who has done their requisite stint in London and wrote immediately to the Art Gallery of New South Wales to complain about the lack of Australian art on display in its collection and admonish their emphasis on international artists over local ones. How things have changed. He even painted a self-portrait to immortalize that stage of his life, in which he sports a red fez and carefully groomed facial hair, suggesting he envisioned himself as the very image of worldliness so many of us do once we’ve Lived Overseas.

Imagine, then, what Russell would think of John Russell: Australia’s French Impressionist, open now at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, a fascinating survey of the life and work of Australia’s forgotten impressionist. In today’s pop cultural parlance, Russell is a ‘Who’ in world of art history ‘Thems’, and the show does a great service when it comes to shining a light on his remarkable body of work, which was shaped as much by the often tragic events of his life as the immortal notaries who would have an indelible impact on it.

That first work in the show, the watercolour self-portrait from 1883, is one of the last works Russell painted before leaving Australia for 40 years. Winnowing in on what makes Russell so fascinating, exhibition curator and head of Australian art, Wayne Tunnicliffe, says that the artist necessarily complicates our understanding of Australian art history, existing as he does both within and outside of our understanding of impressionism in particular. At a time when, locally, artists were flourishing at a time of emerging nationalism and the most popular subjects were, put simply, national subjects – the landscape, the toils of masculine labour – it’s significant that our most impressionist of impressionist artists, if you consider France as the movement’s origin point, wasn’t even in Australia at the time – he was painting in France with The Impressionists themselves. “He’s an artist that sits within and without, in this wonderful position that complicates our art history,” Tunnicliffe said last month at a preview of John Russell. “He’s also just a really fantastic painter. He began with academic training, moved into the French avant-garde, encountered extraordinary artists, had to throw away everything he learned to that point and embrace a new style and a new method.” What becomes very apparent in the show is just how experimental Russell was, how, when he hit his stride, he became a great artist with an extraordinary his ability to bend light and colour to his will.

Of the 115 works included in the exhibition, 90 have come from other collections around the world, including the Van Gogh Museum, the Musée D’Orsay, the Musée Rodin, and the Philadelphia Museum, as well as private collections across Europe and Australia, particularly from Russell’s own descendants. One such example of the latter is a series of drawings created soon after Russell arrived in Paris of a supposed artists’ model he took as his mistress, the Italian Anna Maria Antoinetta Mattiocco, or, simply put, Marianna. Russell became obsessed with her beauty and physicality, as depicted in the erotically charged pencil drawings in the classical Slade style of the mid-19th century that remain in the family.

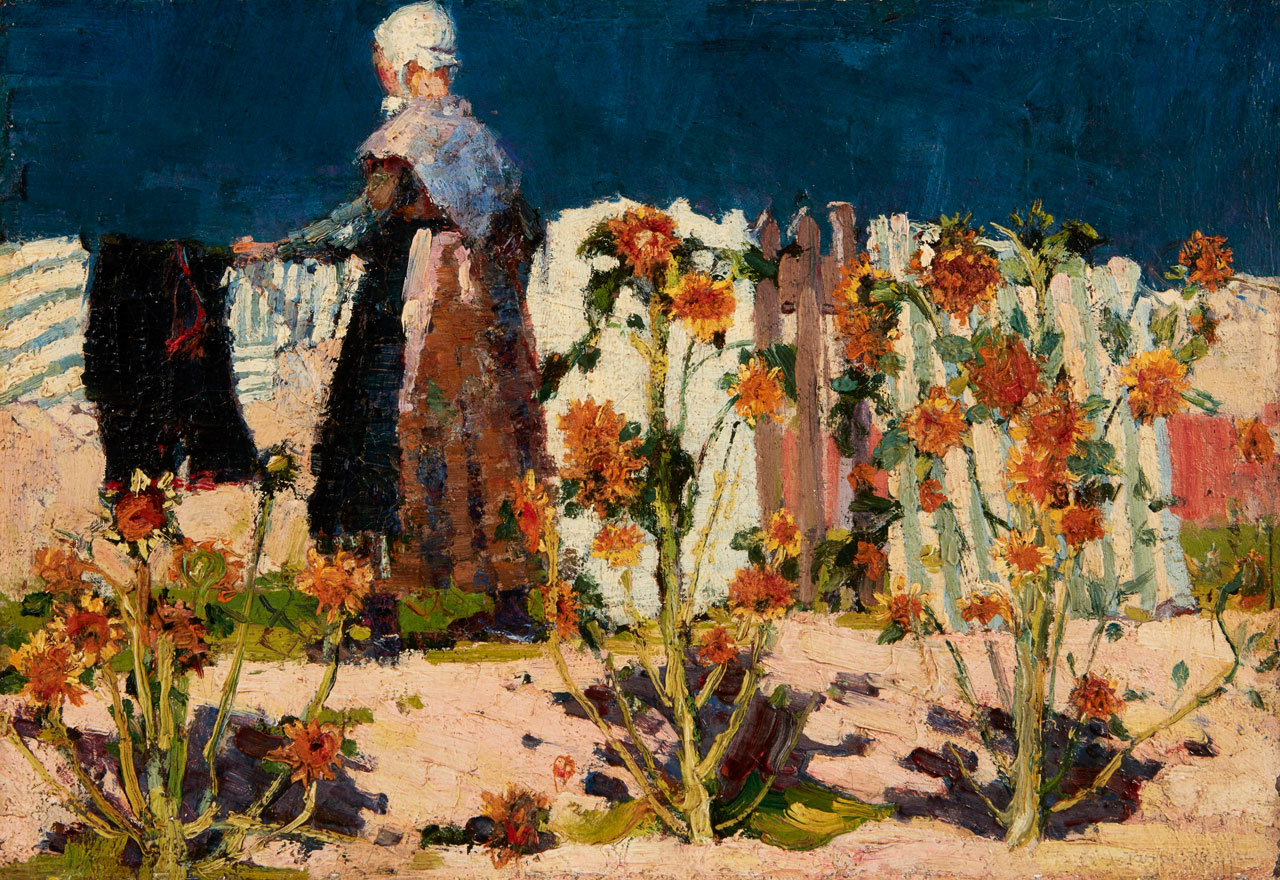

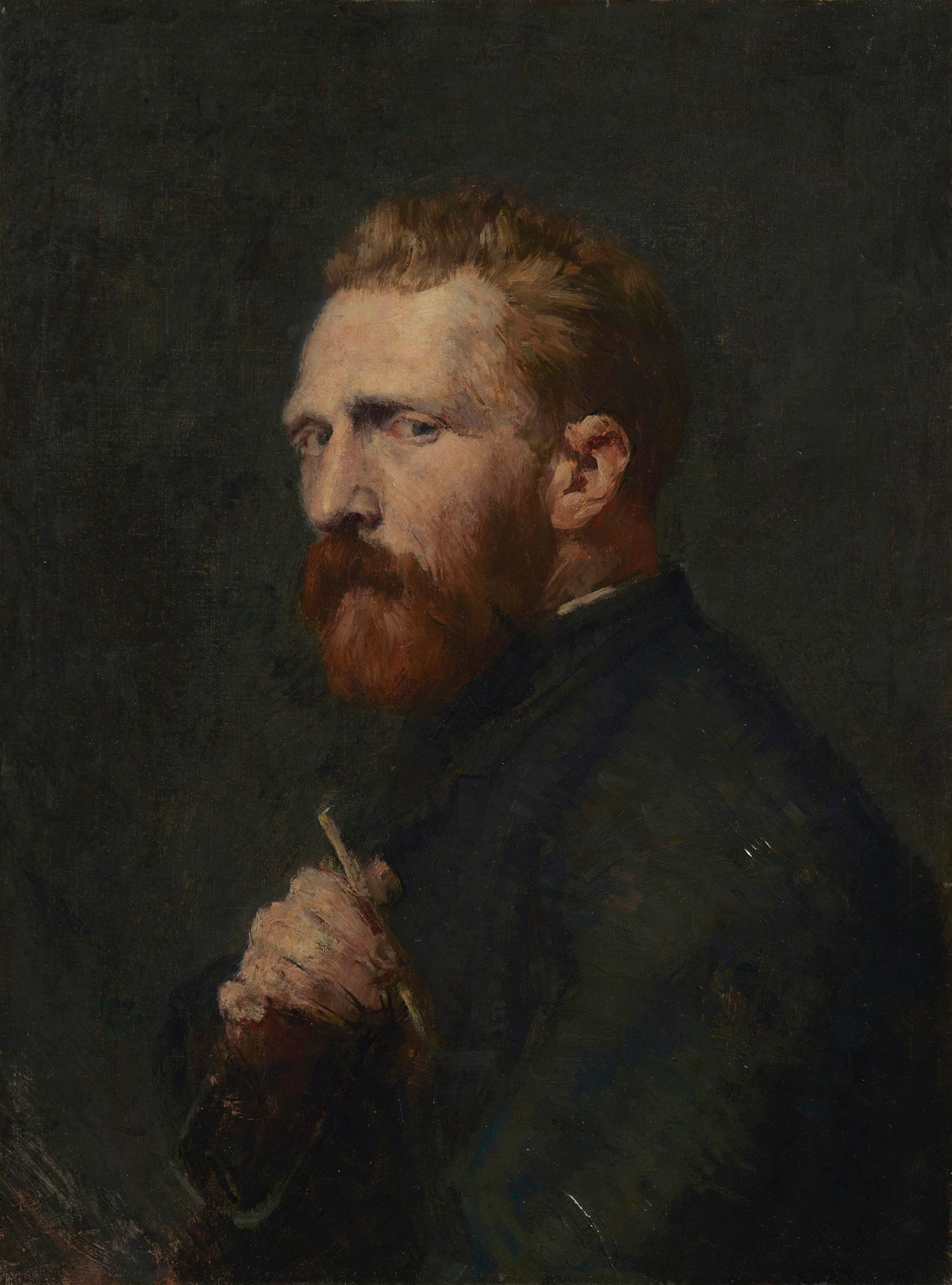

In Paris in late 1884, Russell joined small teaching studio in Montmarte of just 35 students, the ranks of which included Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, one of the many young artists in the cohort who would go on to shape successive phases of French art. In 1886, a tempestuous young student joined the academy and soon struck up an accord with Russell – the then unknown but no less divisive Vincent Van Gogh. The two fast became friends and would visit each others’ studios and even painted alongside one another, depicting the same subjects (Peasant woman with sunflowers). Included in the exhibition is a kinetic, poignant portrait of the Dutch artist by the Australian presented alongside a self-portrait, both depicting Van Gogh in dark tones four years before his death. A neighbouring pen and ink on gouache drawing, Haystacks (1888), by Van Gogh, is one of 12 gifted by the artist to Russell, who would later give the same drawing to a young, unknown art student who visited with him on the island of Belle-Îlle-en-Mer in 1895, where Russell later lived. That student was Henri Matisse, whose works also feature in the exhibition, and who returned over successive summers to visit with Russell and discuss the impressionist techniques and colour theories that would ignite his career as one of the great artists of the 20th century.

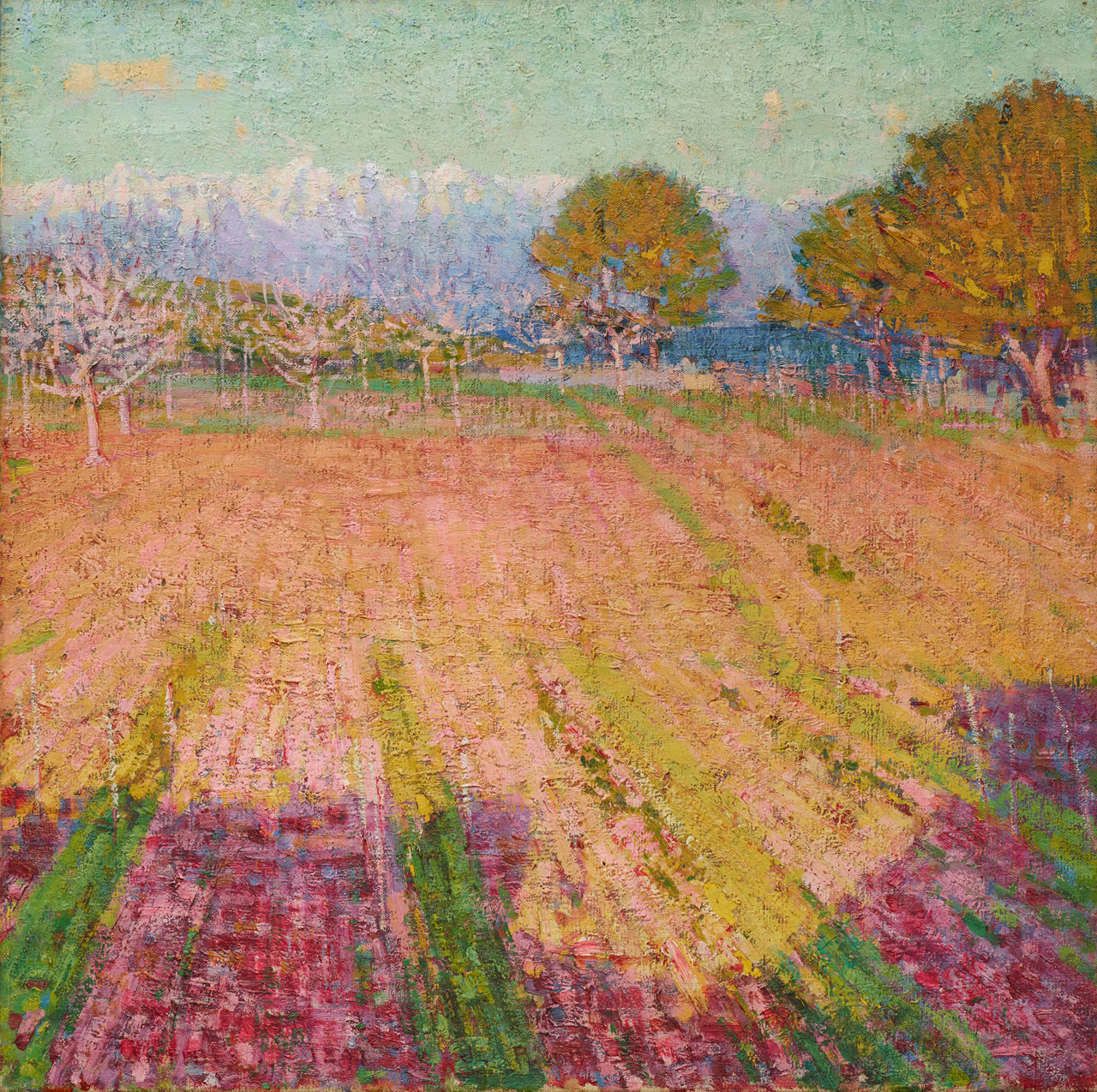

In a neighbouring work, Almond trees and ruins, Sicily, a landscape painted en plein air in a naturalist, high-Impressionist style with relatively high key colours and evident brushstrokes, an almond blossom lies entombed in the work. It was on the same trip that the artist’s son with Marianna, Jean Paolo, died suddenly. A prolific penman, Russell wrote of the tragedy, amongst many other things, in hundreds of recovered letters to his contemporaries. When Russell and Marianne decided later to marry in 1888, the artist sought out the talents of Auguste Rodin, and commissioned the sculptor with creating a bust of Marianna. Taken with her classical beauty, Rodin, who at the time was not taking private commissions, made innumerable casts of her likeness to be used in later works inspired by women of antiquity. Twelve remain in the Musée Rodin wrought from marble, bronze and silver, and they feature in the exhibition in the round. The connection would last a lifetime, with over 60 letters unearthed by the curatorial team between the two artists exchanged over the next 35 years prior to Rodin’s death in 1917.

Not all of Russell’s friendships were as lasting as those he enjoyed with Rodin, amongst others. Having temporarily relocated to the island of Belle-Îlle-en-Mer off the tempestuous coast of Brittany in northwest France in 1886, Russell by chance met Claude Monet, whom he addressed as “the prince of the Impressionists”, while painting atop a cliff. The two dined together often, and even painted together (on one particularly fateful venture, they got stranded in a cove and had to be rescued by fishermen). Port-Goulphar, Belle-Îlle (1887), a densely layered Monet from the Gallery’s collection, is one of several of the artist’s works that features in the show, and his influence is palpable in the adjacent works produced by Russell from the same time, as well as all those produced after. Russell soon bought land on the island at the head of Port Goulphar, where he and Monet first met, and he remained there for the next 20 years, travelling further afield only to visit Antibes and the Côte d’Azur, where the clear Mediterranean light and colour fascinated him (he did, however, despise the tourist population). The works he produced there en plein air are incredibly complex and confident in their embrace of impressionist technique, and speak to Russell’s dramatic growth as a colourist. A series of wave paintings all painted from the same position on the dramatic cliffs of Belle-Îlle overlooking the Atlantic Ocean are remarkable, gestural works painted in high-key colours with expressive brushstrokes that evince his later growth into a post-impressionist style.

When Marianna died of cancer at 42 in 1908, Russell all but ceased painting. He sold his properties on Belle-Îlle and in Paris, focusing instead on his daughter’s career as an opera singer before travelling Europe, during which time he documented his experience in watercolour and assisted with the war effort in London. Russell returned to Australia in 1922, and settled in Rose Bay. This time around, however, he no longer engaged with the relatively conservative Australian art world, and there’s no mention of any curmudgeonly letters sent to the national broadsheet decrying state art institutions. Instead, it sounds as though Russell was content to resettle into family life and paint his native harbour in the same colours as those he used to depict his one-time home in France. The show closes with a final work from 1907 depicting Marianna in their garden of flowers at Port Goulphar rendered in visceral, almost pointillist layers. The paint has been built up to the point of protrusion, appearing so three-dimensional as to almost reach out. All that remains is for Russell’s final impression to be left on you.

John Russell: Australia’s French Impressionist will exhibit at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until November 11. More information is available here.

Tile image: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (State of the Netherlands)/Photo: Maurice Tromp

Cover image: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, purchased with funds provided by the Art Gallery Society of New South Wales 2016 Photo: AGNSW, Mim Stirling