News feed

The National Gallery of Victoria is currently playing host to two complementary exhibitions that explore the art that has emerged as a response to Australia’s fraught colonial history. Presented concurrently, Colony: Australia 1770–1861 and Colony: Frontier Wars explore the colonisation of Australia through a comprehensive survey of differing perspectives provided by historical and contemporary works that have been created by Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists working from the pre-contact era to the present day. The erasure enacted by the practices of colonialism over centuries means that, for many, ‘identity’ as a concept has been lost to time. Through challenging global museum conventions, Colony: Frontier Wars in particular credits the subjects and makers of anonymous photographic portraits and historical cultural objects as ‘once known’ rather than ‘unknown’.

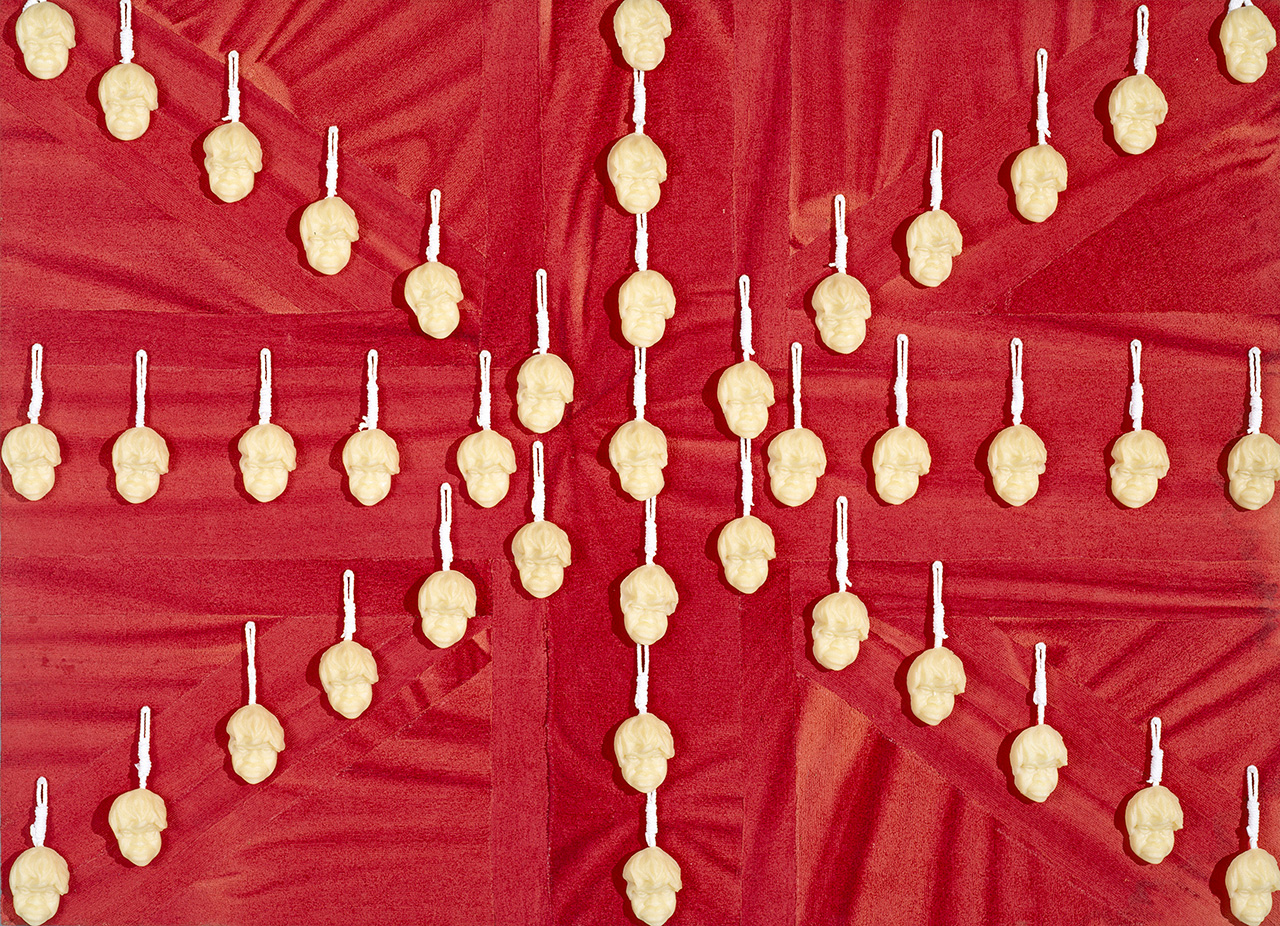

Exhibiting her work as part of Colony: Frontier Wars is Julie Gough, a Trawlwoolway born multimedia artist whose work is largely preoccupied with the dark colonial history of Tasmania, and in particular, her traditional Tebrikunna country in the far north-east. Two of Gough’s works – a breathtaking sculptural installation and a mixed-media work work – appear in Colony: Frontier Wars. Below, Gough discusses the concept of ‘identity’ in relation to her expansive art practice and one work in particular, Observance.

In this video work, featured below, words appear across the screen as though floating in the sky. As Gough says, “these are the words our ancestors introduced to language before speaking our languages [was] banned in the 1830s. These are the last words and phrases for things introduced by the colonists: muskets, knives, tents, and also sheep [and] dogs. It ends with he ominous word for ‘hang by rope’.”

This article is part of a series originally published in the March print edition of GRAZIA, out now. Subscribe to receive your copy here.

As a child, I was an introvert. I’m still an introvert. I had a bit of an imaginary world, in a way. I was always interested in going from macro to micro and back and forth. I watched what was going on around me with people, but also objects.

I’m a curious person, and so my personality is trying to unpack things and reconstruct things. It hasn’t felt like I became an artist, or I changed anywhere between age 0 and 20. It became a term for it; ‘artist’ became a way to do this stuff without being arrested.

I can’t say there’s a moment when anything changed, in terms of trying to process the world, it’s just that I became more aware of my family history on both sides. It’s still an ongoing journey for me to understand what has happened with all of my ancestors, and having been born and grown up in Australia, it’s probably more natural that that is where I feel most connected. I felt always something, like a magnet, to Tasmania.

The full experience of life is here. This feeling of the area’s always been in me, it’s correct. Rather than feeling like I’m on some sort of weird life support everywhere else, and I could die. Other places are exciting, but it’s almost like I’m scuba diving everywhere else, but here I’ve got full use of my lungs.

I didn’t grow up with seeing Tasmanian Aboriginal as anything that I was consciously aware of. I hadn’t understood what being Tasmanian, our Tasmanian, meant. It really is an interesting situation. I always say, this is my strange way of wandering the world. I hadn’t fully processed who we were until I moved back here, met more family, and realised that it was serious.

To be who I am, I have to step up. To me, it’s not an option to just work a nine to five in a bank and be in a void. All of the things that brought me back here, which are things I don’t even understand, have sent me on [what feels] like a predetermined path to be here and to try and communicate what has happened here, because I’ve got this strange capacity to make work that can take people who wouldn’t go to the archive into our history with me.

Observance came about because I was invited to be in an exhibition, Deadly: In-between Heaven and Hell. That’s what brought it to mind, was, what is something between heaven and hell? It’s actually my home territory, my home country, in the Northeast of Tasmania, where my family haven’t lived since the 1830s; no Aboriginal people have lived since the 1830s. I said, “That is my heaven, and the reason it’s my Hell is because every day most of the year, but summer more so every day, a group of about eight to 10 eco-tourists are going on the Bay of Fires walk.”

If you’re on the beach or in some of the hinterlands, they’ll just be there. They interrupt you every day. You might be thinking or feeling through time. Up there, you can hear things that aren’t right now. It’s very strange, like a portal feeling, up there. You feel like there’s a ripple of time happening. They are this strange arrival that interrupts what connection you could be having on that day through time with your ancestors.

They’re not there to connect with country. They’re just kind of sleepwalking across country, basically. They’re just trying to wind down and be somewhere beautiful but not cultural, really. I can’t say that for all of the many, many, thousands of people who have done this walk.

The film is like that. Me observing them, from a distance and up close, right there, right next to their feet. You find it hard to recognise anybody, but I’m observing [them] the same as my ancestors would be observing the new arrivals through any period from the 1700s onwards.

By doing that and filming those visitors, I became [an] ancestor, in a way. It actually was slightly exciting and terrifying at the same time. I felt like I could be found and violence could be done to me. It felt like I am shooting them, almost, with the camera, but in a way, they could turn on me. It felt very subversive.

Filming at that time didn’t feel empowering. It’s more when I see the finished film and I watch [it], I’m glad that I captured them doing this thing. Someone said to me, “The ethnographic gaze is always on the native, on the exotic person, and you’ve reversed that camera.”

It’s this idea about respect. I’m not necessarily respecting them, but I’m thinking about my country and what’s happening to it. It felt that [Observance] was the term that was appropriate for this place that is our church. It is equivalent; it’s sacred.

Colony: Frontier Wars will exhibit from 15 March – 2 September 2018, at NGV Australia at Melbourne’s Federation Square

Tile and cover image: Courtesy of the artist/Eugene Hyland