News feed

At its longest and widest points, it is no larger than a football field. But in Hanifaru Bay – laying as it does along the outermost rim of a thumbprint-shaped cluster of islands, coral reefs and sandbars known collectively as the Baa Atoll – you quickly lose grasp of the scale of things.

Though the bay itself is less than an hour’s flight north of Malé, the capital of the Republic of Maldives, it feels as though you’re so far from solid ground that you could never conceive of being anywhere else. Buoyed in part by the bathwater-warm currents below, the tempest brewing above and the giddy ecstasy of anticipation that exists somewhere in between, it’s almost as if you’re not only bearing witness to another planet but intruding on an entirely new and private realm.

Within the 1200 square kilometres of the Baa Atoll are 75 islands, of which only 13 are inhabited. Many in the latter camp are swept daily of the flotsam that’s deposited by the tide before the sun has finished rising. Anything that’s blown toward the sea from the dense evergreen heart of the islands barely has time to settle before it’s whisked away. Most of these islands wouldn’t take more than an hour to circumnavigate by foot; it’s faster still if you’re afforded two wheels or two flippers and a favourable current to call your own.

Baa Atoll is home to what may be one of the most complex ecosystems in the world. In June 2011, UNESCO declared the region a Biosphere Reserve; it’s the only one in the 298 square kilometres comprising the Maldives. Here, the land, reef and sea alike teem with life against all probability. There are large-mouthed groupers and spotted-eagle rays; iridescent parrot, butterfly, lion and damselfish; somnolent turtles and magnificent giant clams. Species whose odds of survival are becoming increasingly uncertain. Then there’s the region’s megafauna: the whale sharks and the manta rays. It’s in pursuit of the latter that we’ve travelled thousands of kilometres, although – as our 45 minutes floating in an increasingly turbulent Hanifaru Bay expires – it looks like all that time spent in transit might have been for naught.

Of the 1200 islands in the Maldives, most are uninhabited. As the ebb and flow of the tide and monsoon winds deposit sand and coral into growing embankments, new coral islands begin to take shape at the ocean’s whim; the rate at which they’re growing, however, is far outpaced by the rates at which the seas’ temperature and acidity are rising – two of the greatest threats to the vital coral reefs that gild these parts of the Indian Ocean. During the most recent El Niño (a warming of the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean) in 2016, temperatures reached as high as 40°C in some parts of the sea. Where ordinarily the surface temperature might subside two metres beneath the surface, those extremes continued as far as 40 metres below. Apparently, you’d need a cold shower as soon as you emerged. Nothing should exist here but fish and coconuts. That a reef or an island alike can sustain an entire universe within itself is nothing short of miraculous.

It was an unusually grey day when I arrived on the Baa Atoll’s Kihavah Huravalhi Island, home to Anantara Kihavah Maldives Villas. The Maldives’ unusual approach to tourism, in which each island sustains a single resort, means that island and resort often feel symbiotic – as though one could no longer exist without the other. In the case of Anantara Kihavah, which is a 35-minutes seaplane flight from Velana International Airport in Malé, it’s a supposition that feels close to the truth. The island boasts 79 private pool villas which, whether built over the lagoon or ensconced within the verdant centre, are the epitome of a luxury that again starts to feels other-worldly – the sole purview, perhaps, of a lucky few.

Only five days earlier, Leonardo DiCaprio allegedly arrived on the same island with 23 Victoria’s Secret Angels in tow. A lunch, orchestrated by Paris Hilton, took place at the underwater dining room that anchors the resort’s four-pronged dining experience, Sea.Fire.Salt.Sky. The restaurant, aptly titled Sea, is all glass walls in the round facing outward into the open ocean. It clings to the precipice of a vertiginous reef that slopes gently to a point before plummeting 60 metres down into a channel below. At these depths, it’s impossible to shake the feeling that, in less fortunate circumstances, it would be you and not the sea bream who was most deserving of a place on the four-course tasting menu. To dine in such surrounds invariably raises any number of questions. Chief amongst them: What did Leo and his companions discuss as clouds of cardinal fish swam by? What ideas were exchanged as parrotfish sparred with golden trevally, and fluorescent clownfish took shelter in the coral forests below – embarrassed, perhaps, that the group’s beauty paled in comparison to their own? All things considered, it would be only fitting that talk should turn to the environment. Specifically, the one in which you find yourself submerged.

In 2017 marine biologists from Coral Reef CPR, a small not-for-profit charity led by coral reef ecologist Andrew Bruckner, began working with Anantara Kihavah. The joint mission, one that continues to date, was to implement conservation, rehabilitation and education initiatives at the resort in a bid to restore the reef habitat. This applies not only to the waters surrounding Kihavah but to a triad of neighbouring island resorts that also belong to the Minor Hotel Group: Anantara Dhigu, Naladhu and Veli.

Over a period of 18 months, the corals damaged by man and nature (namely, the virulent crown of thorns starfish) alike were cultivated and treated in aquatic nurseries before being painstakingly reintroduced to the reef. In the process, it was discovered that some varieties, now affectionately dubbed ‘super corals’, were able to tolerate the higher temperatures. Some turned an even more brilliant shade of iridescent blue, or did not leech their colour at all. It’s faint, but what remains is something resembling the beginnings of a silver lining. You can see the resort’s coral nurseries, half a dozen ropes suspended in the water of a dark blue channel, from the arrivals jetty at Anantara Kihavah. There’s another nursery near the resort’s dive centre, and it’s from here that you embark for Hanifaru Bay.

In inclement weather, the task of finding a manta ray in the bay is not dissimilar from finding a needle in the world’s largest haystack. While each of the Anantara resort islands is framed by waters that are as welcoming as they are lucid, it’s a different story in Hanifaru Bay. No longer azure blue but an inky black, the ocean is near opaque with plankton – a promising sign that this second visit will yield more success than the first. I climb up onto the side of Ocean Whisperer, the yacht that’s ferried us to Hanifaru once again, and stand sentry next to Bruckner, a stoic and well-sunned Washingtonian whose gaze is fixed unfailingly toward the vast, pounding ocean even when he’s on solid ground. It’s not long before a delicate wingtip no larger than a paperback breaches the surface. And then another. And another in orderly procession.

Imagine you’re floating face-down in water, immersive and warm like velvet. There’s nothing but ocean around you – the dive boat long-gone, no other snorkellers and no end in sight. An ocean of noise fills the space in between you and the unending void; the only sound is that of your own breath as it ricochets in the hollow of the snorkel that keeps you tethered to the world above. The silence is huge, at once profound and profoundly unsettling. As the sensation of your incompatibility with your circumstances begins to crest like a wave threatening to bear down upon you, you spin around.

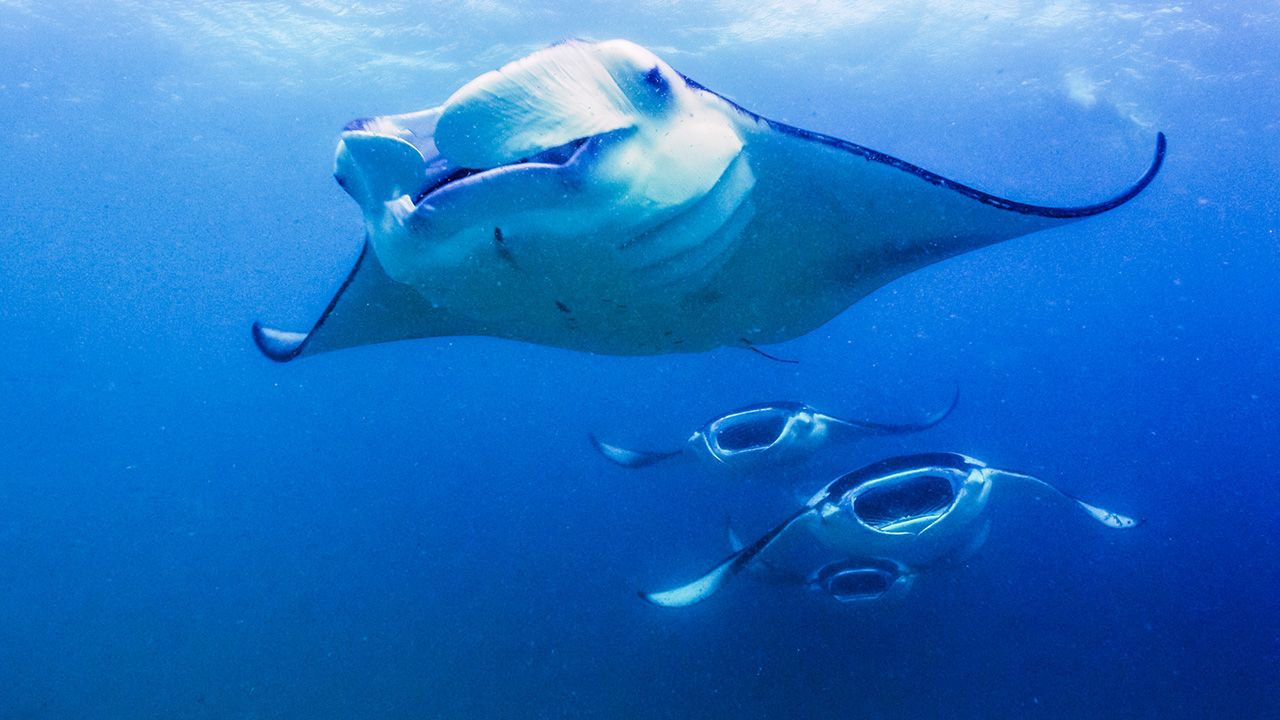

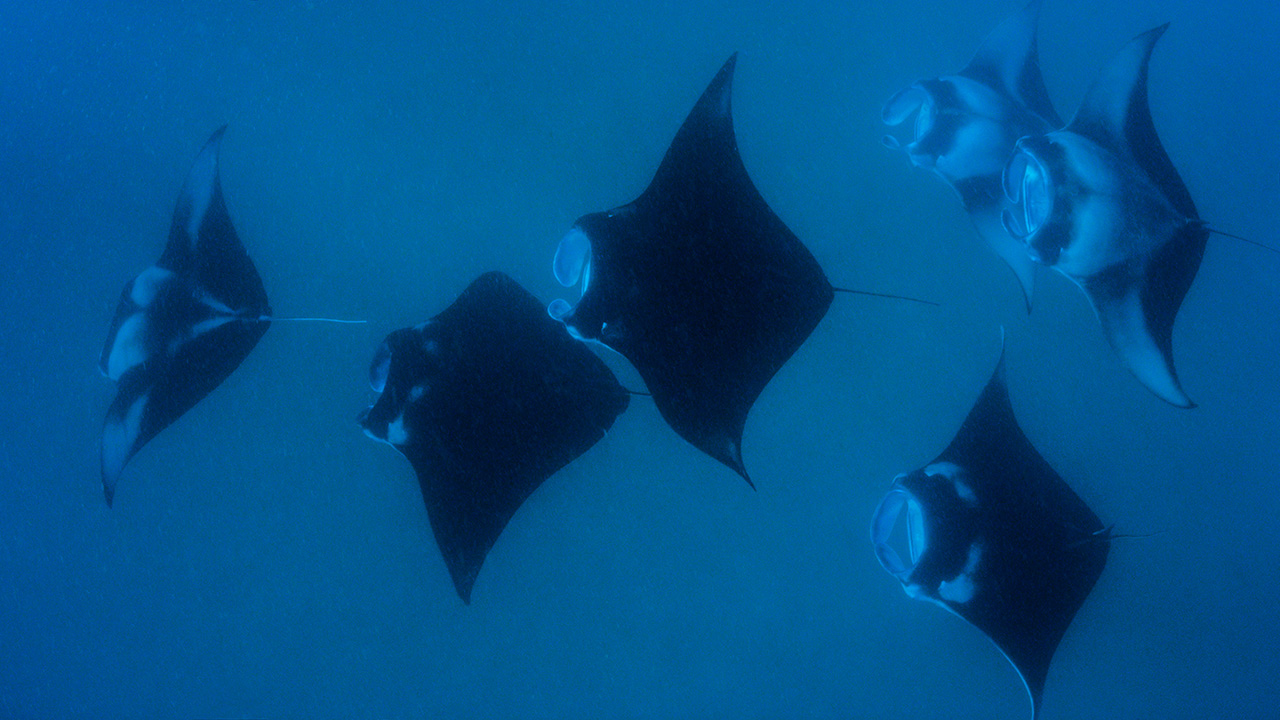

Manta rays travel, feed and mate in chains. One of those chains, party to some 27 rays, is now barrelling toward you in what can only be described as a balletic soul train. For the better part of an hour it will entertain you with a private show as it dances along the edge of the bay until the seabed slopes off into the impenetrable darkness and the rays gently hovel whatever they can into the abyss of their maw.

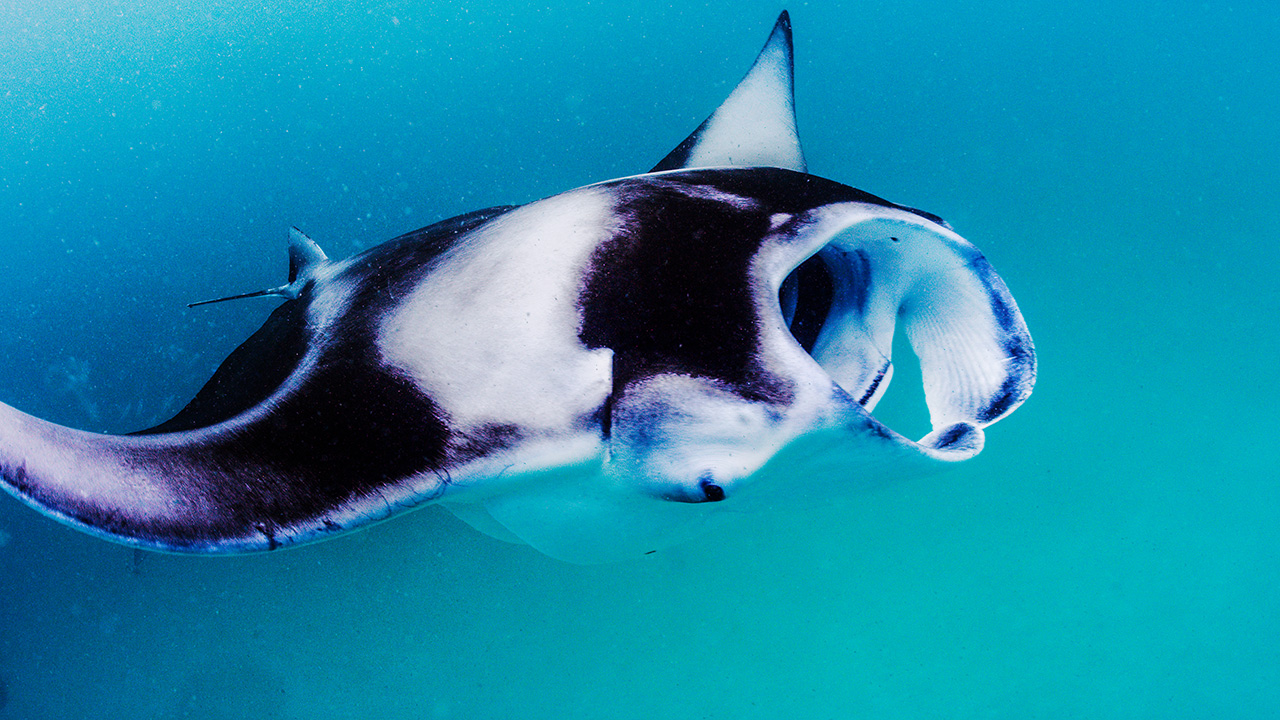

Here is everything I know now about manta rays. The largest female will invariably lead the chain, the men following suit. Their gullets are wide, but pale in comparison to their wingspan, some of which measure in excess of six metres. With fleshy wings, the female will perform the steps to a highly choreographed routine. Like the early rounds of a dance-based reality TV show, the men will replicate those movements and, if they get a step wrong, are forced to the back of the train. Eventually this extensive courting ritual whittles prospective suitors down to a single mate at the head of the pack, to whom the female will bear a calf once every two to three years – but only after she has reached sexual maturity aged eight to 10. Their indecisiveness, coupled with a laissez-faire approach to fertility and reproduction over the course of a long life, accounts for part of the reason why this magnificent species is listed as endangered (though its largest population congregates here in the Maldives).

Manta rays’ stomachs and wings, which expand with age, are covered in permutations of black, white and grey. Their skin appears soft to the touch like mohair (touching, however, is forbidden), the edges of each marking blurring into the other like a Rorschach test that doubles as a unique fingerprint. They move with all the grace of a chorus line that’s gloriously out of sync, each dancing a beat behind the other. Some break free and steal the stage with a rousing solo performance: a freewheeling somersault that’s part play and part going back for a second serving. Their acrobatics are the equivalent of herding the plankton; like peeling an orange, they spiral around and around, narrowing the playing field until everything is condensed into a single, continuous gaping mouthful. Their eyes, set in the sides of their head, are pearlescent and unmistakably kind. They’re finely attuned to the movements of their company – at no point do they collide, even when they double back; they duck and weave as though compelled by a shared frequency that both attracts and instinctively repels its own kind.

The after-effect is a dwarfing one. A humbling one. The best travel often calls for little more than taking yourself out of a familiar environment to experience something bold and new: a liberating and terrifying glimpse at just how small, how infinitesimally microscopic you are compared to what lies beneath and above. I imagine it’s how the plankton feel.

The following morning, and each thereafter, everything felt significant – the smallest things were suddenly rich with meaning. The birds wheeling overhead as I rounded the peak of Kihavah Huravalhi became a chorus whose only role was to imbue every natural phenomenon with what seemed like life-altering significance. Though it was dawn, the sun beat down strong on the deck of Kihavah’s overwater spa where, during an Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga class, the correct assumption of a pose was marked by the fanfare of a visiting pod of dolphins or the sight of a seaplane arriving from Malé, its wings cast in stark relief by the sun rising over the sea behind it.

On another island, Veligandu Huraa, home to the deeply private Anantara Naladhu, an early morning deep-sea snorkel trip was rewarded with countless close encounters with turtles whose eyes belied a lifetime as old as the reef itself. Each ecstatic sighting not only felt like a harbinger of the next, but an assurance that every day thereafter should and would begin in a similar fashion. Nearby were the twin private islands of Niyama, aptly named Chill and Play. On the latter, the chance to surf the only beach break in the Maldives seemed not only feasible for a complete amateur, but totally risk-free (suffice to say, it is not; the break lands on a shallow reef). A leisurely turn parasailing above the lagoon was no longer just a fanciful way to while away an hour, but a well-considered proposition for all travel going forward.

Even the islands themselves, their contours gnawed into being by the waves that have ceaselessly lapped at them over many thousands of years, began to feel like elaborate sets. Viewed from the seaplanes that ferry guests between resorts and whatever likely palatial home awaits them, they started to look less like arbitrary deposits of sand and coral and more like shimmering cells viewed under a microscope, vibrating with the promise of all that life brings.

Despite their best efforts, the waves have left behind a core that somehow manages to be soft and yet endures still, creating thousands of low-laying isles that are coming precariously closer to the rising sea. If sea levels continue to rise at current rates, it’s believed the Maldives could be completely inundated before the turn of the century. The fact we have the powers to both protect and harm these islands – as well as the vast ecosystems they sustain – verges on tragicomic (veering, perhaps more closely, on the side of the tragic).

Later in the day of my encounter with the manta rays, I lay facing upward in an overwater spa suite as the cautious but willing recipient of an Ayurvedic shirodhara treatment that involved having a litre of hot oil poured directly onto my third eye – another of a litany of experiences that I had never encountered until then, and one that I will likely never encounter again. The treatment itself was hypnotic, the sensation pleasantly numbing, as the oil bore from an overhead fountain into my hairline with no discerning where it might travel next. All it required, if only for a fleeting moment, was total surrender.

Tile and cover image: Courtesy of Anantara Resorts