News feed

Twenty-nine years after it was founded, 20 years after it sent its first exhibition abroad and six years after it formed an Internationally Circulating Exhibitions Program to further its mission as an educational institution, the Museum of Modern Art shipped its first exhibition to Australia.

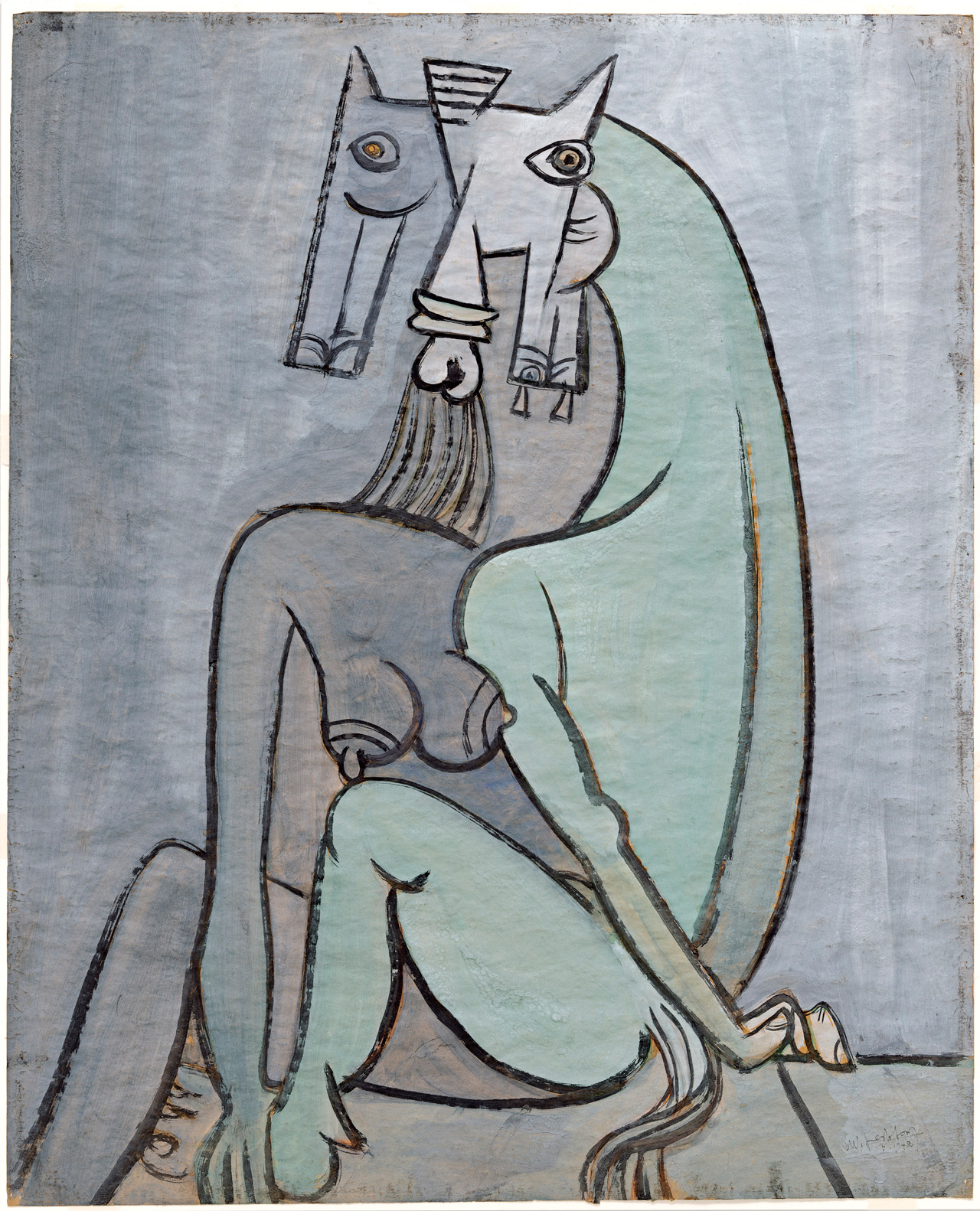

In February of 1958, Contemporary Printmaking from the United States arrived at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Melbourne. The exhibition of 40 prints by 32 artists then made its way to the David Jones department store gallery in Sydney before exhibiting in all other states and in New Zealand, where it would finally disperse the following year. Another blockbuster exhibition of 114 works by 56 artists was staged in 1975. Modern Masters: Manet to Matisse reportedly drew queues that snaked around the buildings at the National Gallery of Victoria and the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Held over the years in between those two shows were 18 others, varying in scale, that pulled from the New York museum’s extraordinary resources – from surveys of individual artists (Picasso: Master Printmaker, 1973) to group shows that dissected pivotal moments recent art history (Abstract Watercolors By Fourteen Americans, 1965).

Though the museum has long made it its mission to share its collections with the world, few occasions have seen them do so on the scale of MoMA at NGV: 130 Years of Modern and Contemporary Art – the 24th Australian exhibition of works borrowed from the MoMA collection, exhibiting now at the National Gallery of Victoria.

MoMA has only staged two other shows of a similar nature in its almost 89-year history. The first, in 2004, coincided with the major refurbishment of their West 53rd Street museum, during which time they sent around 200 works to Berlin for the aptly titled MoMA in Berlin. As recently as last year, an exhibition of a scale comparable to the NGV show was staged at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris (though it was done so with a different curatorial team and a different checklist of works). MoMA at NGV is the culmination of three years of intensive discussions between the National Gallery of Victoria and the Museum of Modern Art, and in many ways, the international exclusive is utterly unprecedented. Rather than emulate one of the Museum’s exhaustive surveys of a single artist’s work, its collaboration with the NGV represents, in a condensed form, over 130 years of progression in art and design featuring a roll call of eminent contributors to both historical canons. “It’s a unique snapshot of their collection,” Dr Miranda Wallace, Senior Curator, International Exhibition Projects at the NGV says of the exhibition, which is structured around eight loose thematic conceits. “It’s not a show that you would see at MoMA, but it’s a show that gives you MoMA in one exhibition.”

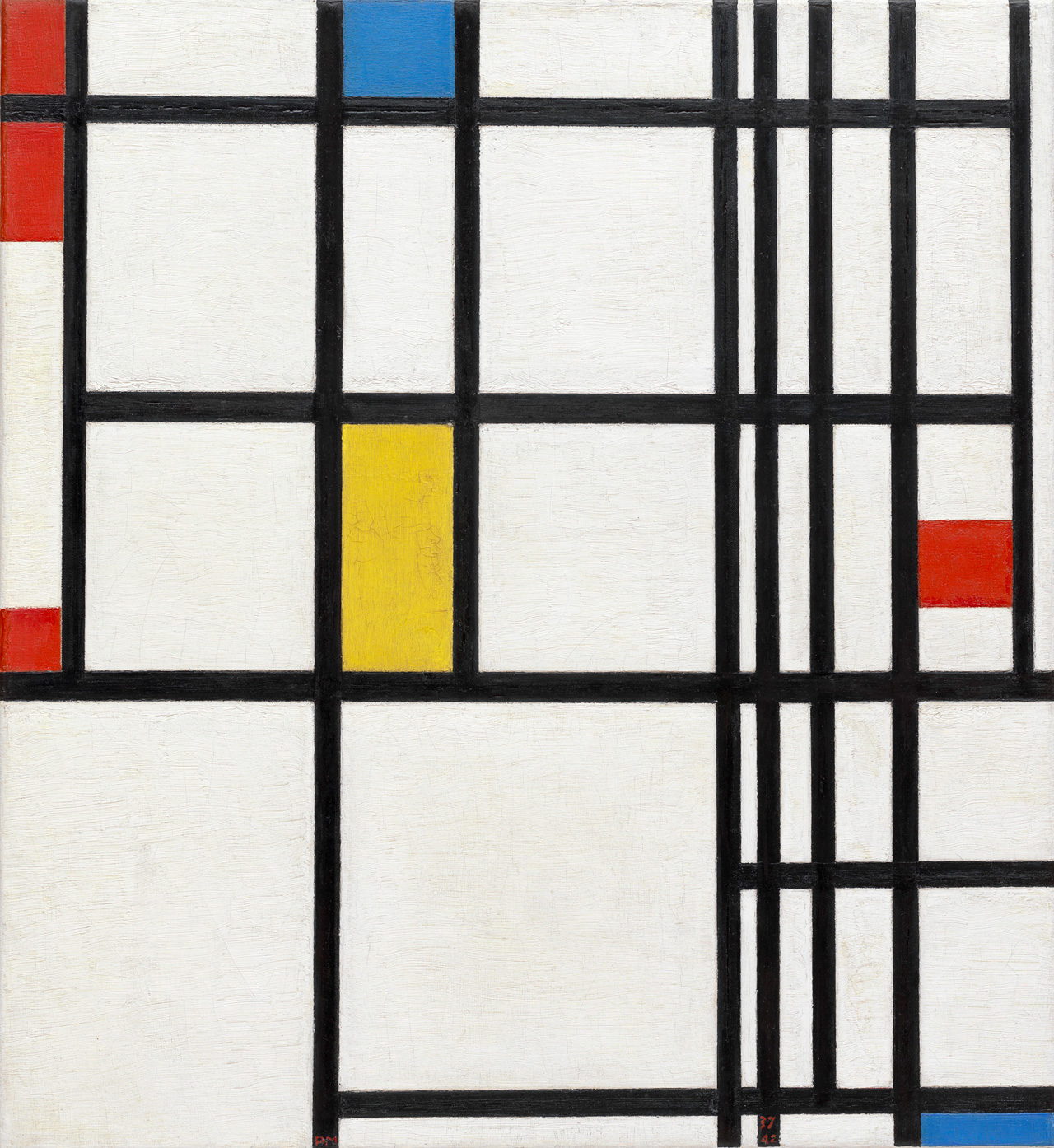

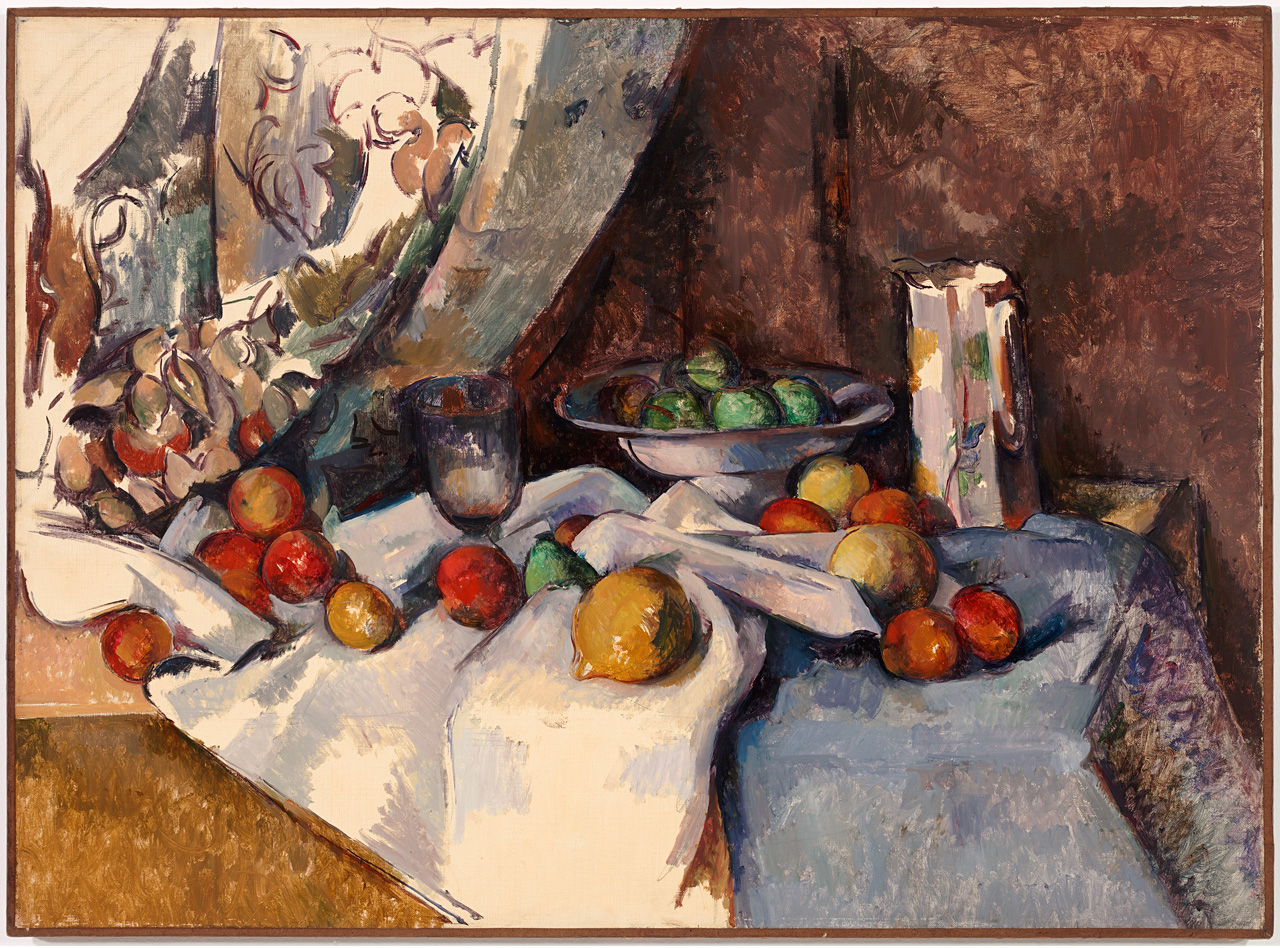

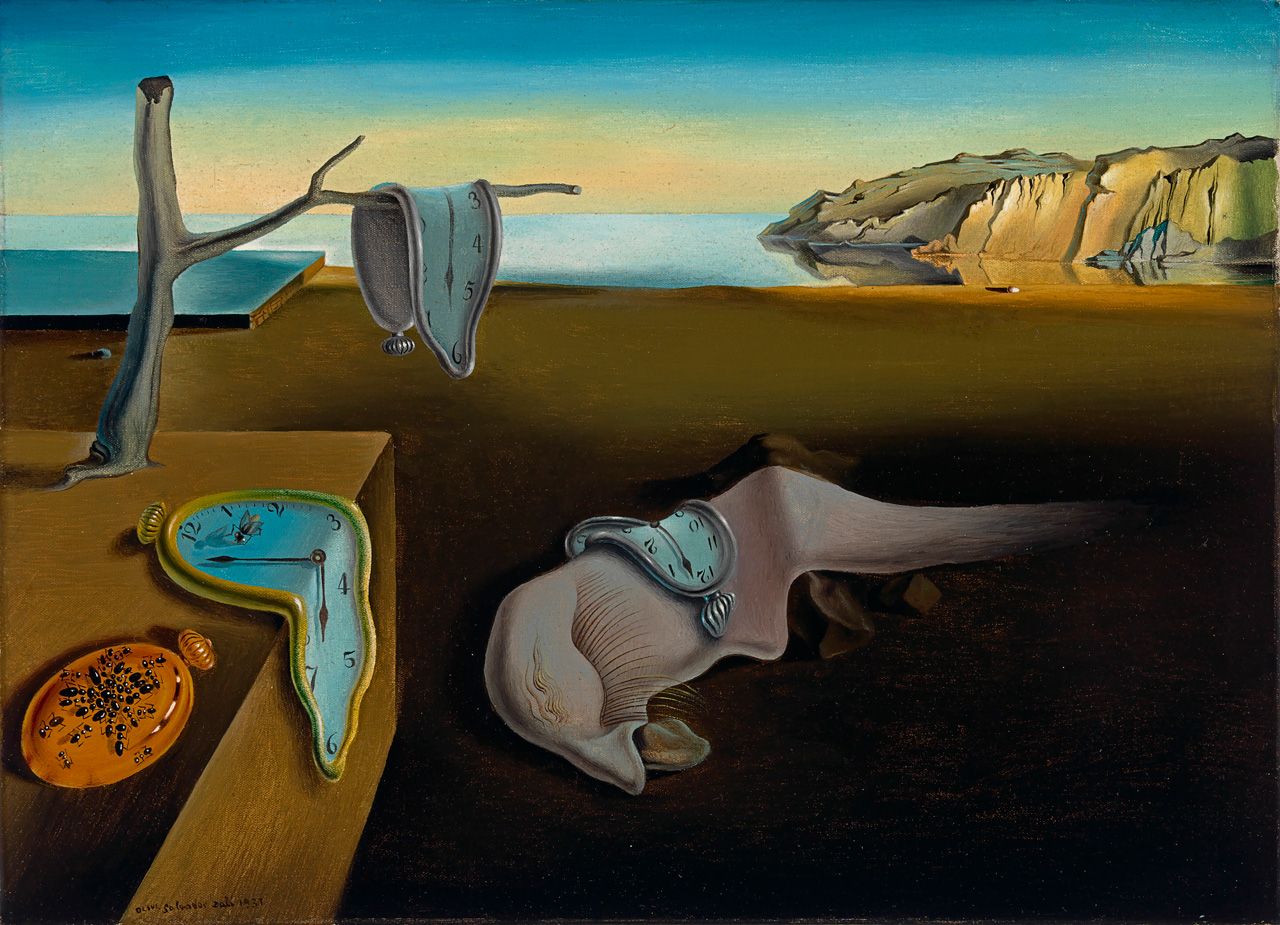

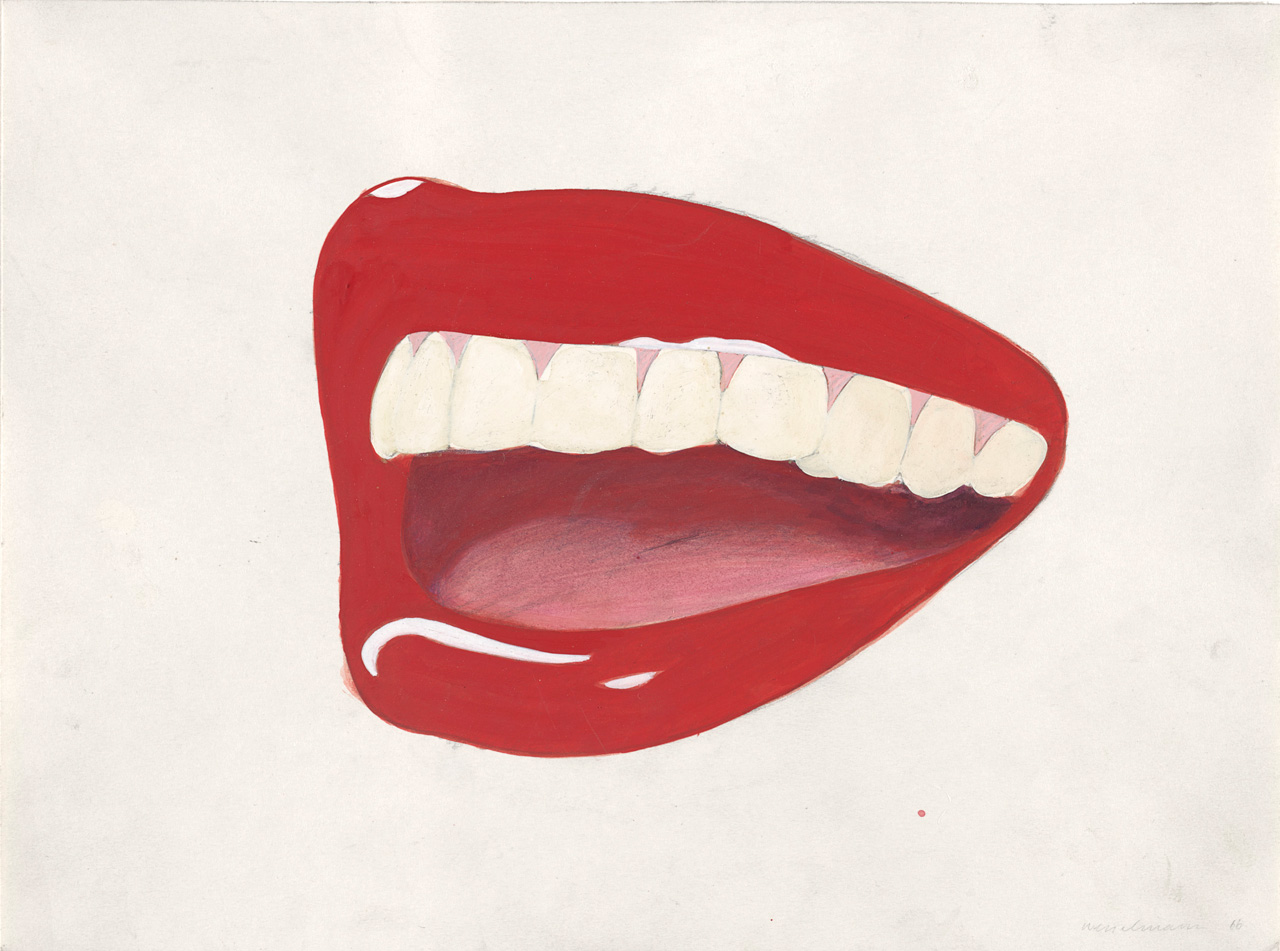

A lot of the works featured in the NGV new show have been loaned from MoMA’s permanent display, and thus will be familiar on sight to many amongst Australian audiences. But to see them reconfigured in a new space and shown alongside other artworks or objects of design works that they would not ordinarily interact with sheds new light on works that otherwise feel innately familiar. Showcasing the museum’s multi-disciplinary approach to collecting and the breadth of its collection, MoMA at NGV features and cross-pollinates works drawn from the Museum’s six curatorial departments: Architecture and Design; Drawings and Prints; Film, Media and Performance Art; Painting and Sculpture; and Photography. Over 200 of these works have never been exhibited in Australia, but even those that audiences are familiar with – say, the lurid Roy Lichtenstein paintings that feature prominently in the exhibition’s marketing materials and figure greatly into MoMA’s aesthetic identity – are brought into sharp relief by the art objects and icons of design that they’re exhibited alongside. “You can never predict, really, the full impact that you get when you have the artworks in the space,” says Wallace. “They talk to each other in ways that you might not have anticipated. It’s a great feeling.”

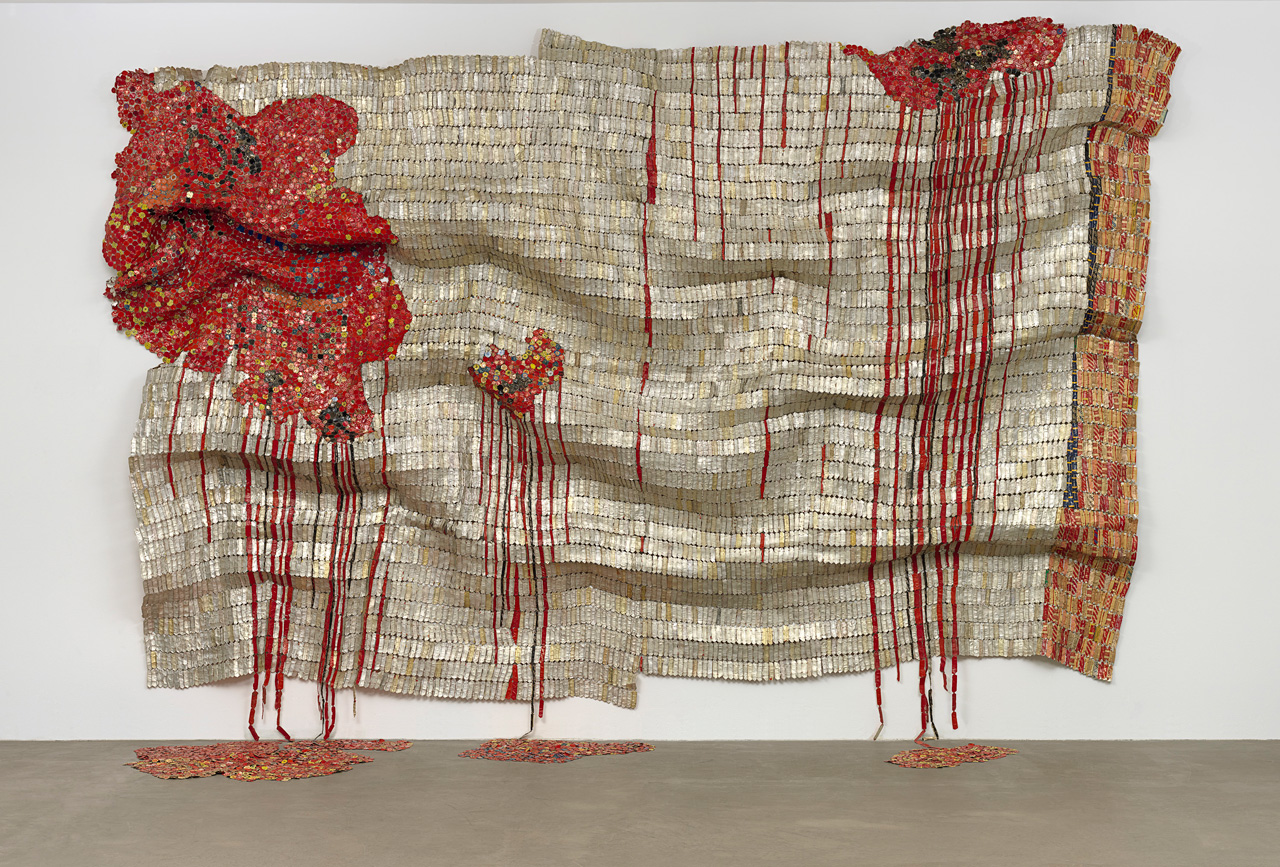

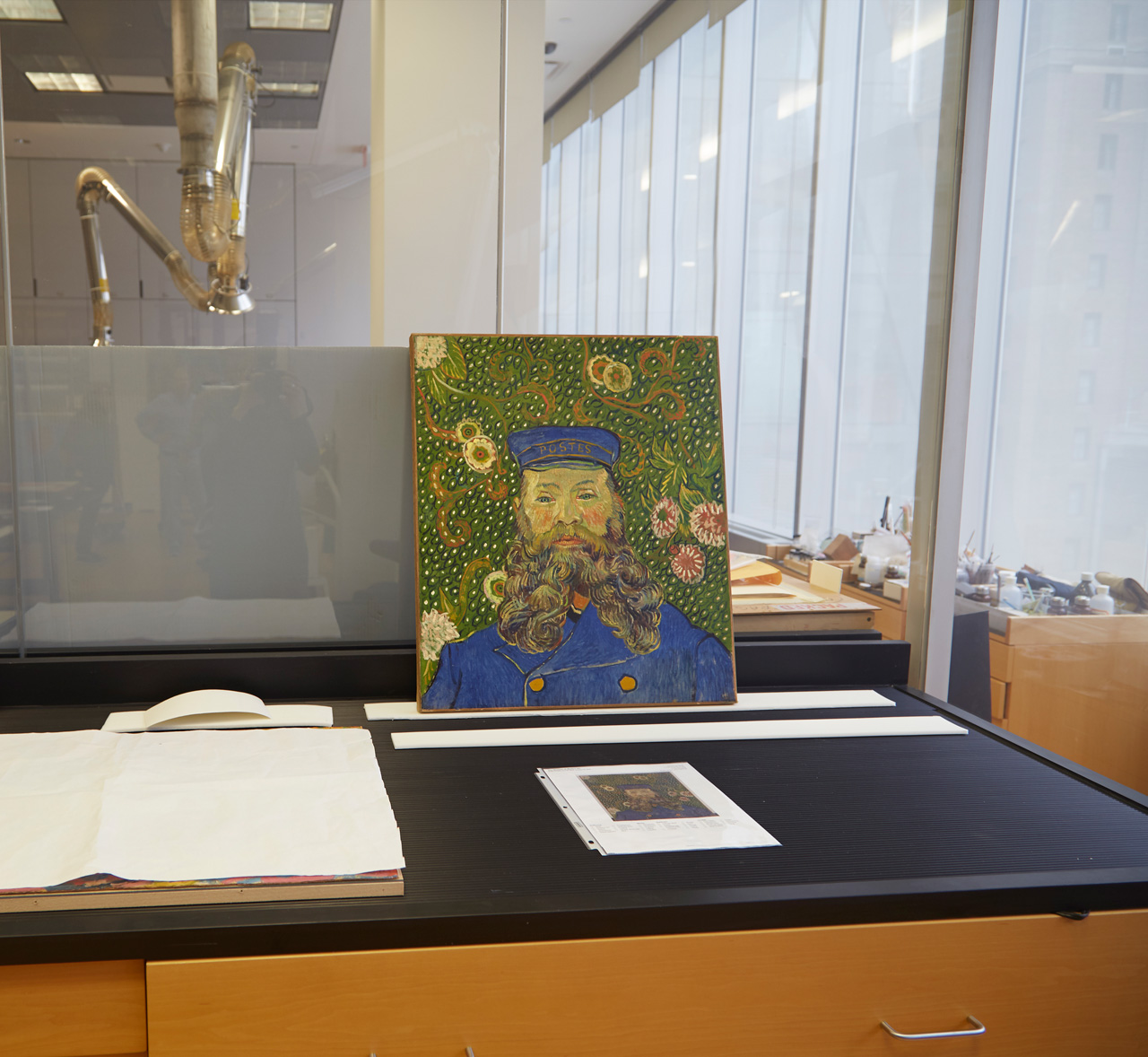

Co-organised by the NGV and MoMA, the exhibition features more than 200 of the most recognisable works in modern art history from a line-up of seminal nineteenth and twentieth-century artists that would exhaust any ‘who’s who’ list of modern art: Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, Edward Hopper, Louise Bourgeois, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Diane Arbus, Agnes Martin and Andy Warhol. Then there are the contemporary artists whose names will perhaps be lesser known to some, but whose impact is nonetheless profound: Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Olafur Eliasson, Andreas Gursky, Rineke Dijkstra, Kara Walker, Mona Hatoum and Camille Henrot. For Wallace, it was the experience of viewing the work of Ghanaian artist Anatsui that proved to be amongst the most moving of experiences on offer in the exhibition. The artist’s gargantuan wall hanging, an assemblage made of recycled aluminium bottle caps, is one of those singular works the magnitude of which is only able to be experienced and understood fully on standing before it and submitting entirely.

The level of collaboration between the two institutions was unprecedented, Wallace says, adding that, in developing the exhibition’s structure and content, hers was an equal voice. Wallace collaborated largely with Samantha Friedman and Juliet Kinchin, both of MoMA, on the exhibition’s development – from reams of early correspondence to site visits and final hangings. Their initial discussions centred on 40 of the most iconic works housed in the museum’s collection created between 1890 and 1960, many of which found their eventual place in the new exhibition, including works from Van Gogh, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Lichtenstein. But a desire to reflect the art of our time, in keeping with the museum’s founding philosophy and continued collecting principles, saw the parameters extended to include contemporary works.

“One thing that we’re wanting to do with this show is really bring MoMA to Melbourne,” says Wallace. “They’re different from an encyclopedic museum. It’s a very distinct experience and I think we’ve evoked that in our exhibition. It is transformative. I think people will feel as though they’ve gone somewhere else after they’ve been to this show.”

While MoMA’s archives include some of Australia’s biggest artistic and design exports, Australian artists and designers represented in this local showing are few. A cursory search of MoMA’s digital archives reveals only 79 out of 25,980 artists catalogued online identify as Australian. Though the purview of the exhibition skews globally in its scope – the late Australian artist and designer Martin Sharp’s artwork for Cream’s second album Disraeli Gears (1967) is one work that features in the show – the emphasis is on the contributions of artists from other countries (such is the purview of the museum’s collecting practice; highlighting those Australian contributions to the archive could also form the basis for an entirely other show, adds Wallace).

Alongside the blockbuster works of visual art that will undoubtedly form the exhibition’s drawcard attraction, also included in MoMA’s permanent collection are a number of performance works, one of which is being restaged as part of MoMA at NGV. “Certainly they have a lot of documentation of performance, which is something a lot of museums have developed since the 1960s in particular, but what they’re [also] doing is collecting the right to recreate works,” Wallace says of the Museum’s capacity to collect works that don’t exist in a fixed, physical sense. As part of MoMA at NGV, the gallery is recreating one of the Italian-American artist Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions, Huddle, as part of their Friday Night program. “It’s halfway between a dance and a sculpture,” Wallace says, explaining the work. Huddle involves nine performers who cluster together into a tightly packed group, or what Forti called a “sculpture made of people”. One by one, acting without a predetermined sequence, a performer detaches themselves from the group and climbs on top of the huddle, while the remaining participants improvise a new configuration to support the new weight they bear on their shoulders. This will be the first ever presentation of the piece in Australia, which Forti first performed in 1961 as part of a larger series of her Dance Constructions in Yoko Ono’s downtown Manhattan loft. “She has worked with MoMA to pass on her archive and there are people at MoMA who are trained to teach and pass on this performance […] so that the work will have an ongoing life in its original form,” says Wallace.

Then there’s the inclusion of other contemporary curiosities that MoMA has begun to retroactively collect in recent years (the emoji alphabet included), beginning with some of the earliest video games, including Pong and Space Invaders. The latter is included in MoMA at NGV in a manner that invites audience participation in a gallery titled Things As They Are, part of the exhibition that encompasses the varied productions of the 1960s and 70s and examines design and artistic responses to the possibilities offered by the future as a holistic concept. Space Invaders features here alongside examples of space-age Italian furniture by Joe Colombo, as well blueprints by the British architects Peter Cook and Ron Herron that reconcile the built environments of their times with boundless visions of the future. Alongside those items are more figures that will be more familiar to present day audiences, but which once would have once seemed entirely alien at the time of their making – the ‘@’ and recycling symbols chief amongst them. “It’s interesting to come back and realise they entered our world as design symbols in 1971 and 1972 [respectively] and had a particular person who designed them and now they’re part of the public domain,” says Wallace.

An exhibition of this scale and cultural magnitude invariably invites questions regarding its assemblage. After all, included amongst the artworks in MoMA at NGV are sculptures of immeasurable value, design objects with swing tags that would beggar belief and paintings the beauty of which is rivalled only by the material wealth they’re emblematic of. How then does one even begin to calculate and describe the logistics of staging such a show in practical terms?

“It’s intensive and long”, Wallace laughs, recalling the arduous shipping process. Thirteen separate transports ferried groups of artworks by freighter and passenger planes from New York over a three-week period, with shipments allocated not only by the demands of insurance policies but also according to measures of scale and their priority when it came to installation. On the other end, the artworks were greeted not only by a comprehensive NGV team, but an escort of 13 MoMA staff. Works like Claes Oldenburg’s Giant Soft Fan (1966-67) required three separate, enormous shipping crates to make the journey; others required that they be double-crated to reduce the potential for damage in transit from external forces (one freight travelled alongside a shipment of racehorses, via Alaska; if anything, it really puts your concerns over your check-in suitcase into perspective).

Luckily, when it came to the video works, performance pieces and typographic works, very little was required by way of shipment and installation – in some cases, only a hard drive was called for. “Thankfully the ‘@’ symbol is just American Typewriter, medium font,” Wallace says, laughing. “You just have to print at whatever scale you want.”

MoMA at NGV will be on display at NGV International until October 7, 2018. Tickets and information is available here.

Tile image: Andy Warhol American, Marilyn Monroe, 1967/The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Mr. David Whitney, 1968 © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

Cover image: Jackson Pollock, Number 7, 1950/The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Sylvia Slifka in honor of William Rubin, 1993 © Pollock-Krasner Foundation