News feed

The last time the American artist Nick Cave visited Sydney, the world felt, in some respects, like a simpler place. It was almost two years ago to the day, and Cave was visiting over the space of a week to stage the transcendent site-specific performance piece HEARD, the first major presentation of his work in Australia.

“We are in a state of despair”, Cave told me then after a dress rehearsal of the piece, sitting outside in the sun at the Carriageworks arts precinct. As part of HEARD·SYD, the fourth iteration of the performance, some 60 local dancers would each don two halves of the same horse-like Soundsuit – the artist’s rainbow raffia-clad signature wearable sculpture – and assume the physicality and psychology of the piece’s eponymous herd. Though Cave’s Soundsuits have assumed many guises, a constant remains in their ability to transform the body, exaggerating proportions and obliterating the identity of the wearer – their race, gender, politics and religion – until they become something entirely other.

The day we spoke was November 8. The following day, the result of the US presidential election would send much of the world reeling. In the days after, Cave and his troupe would perform the work again and again, both at Carriageworks and in the Pitt Street Mall shopping precinct during peak hours. Over time, each successive performance assumed the quality of a salve for the blistering events of the days preceding it. Imagine, if you will, the 30 life-sized horse-suited dancers silently entering a vast public space. Soon after, they begin to buck and bray, trot and nuzzle, before an explosion of rhythmic percussion (courtesy of a dozen musicians from the Matavai Pacific Cultural Arts Centre in Liverpool) causes them to erupt into a riot of colour and movement, at once choreographed and yet with enough space allowed for improvisation. Cave’s euphoric performance was born from an escapist’s desire to stage an intervention in spaces of transition, to ask viewers to interrupt their daily routine and question how we use the time we’re given. HEARD was conceived as “a piece that can stop someone in their tracks” from “a place of pure innocence” inspired by a time in the artist’s life when a sock puppet or a sheet could be used to transform the ordinary into something extraordinary; it was an extension of that childhood naïveté, projected on a much larger scale, and it placed a great deal of emphasis on the responsibility of the artist to collaborate with local communities, allowing for infinite permutations of the piece as both an expression of beauty, sorrow and protest.

The same could also be said to be true of Cave’s latest mesmeric and monumental work, UNTIL, open to the public from November 23 at Carriageworks, which in part co-commissioned and funded its completion in partnership with the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Three weeks prior to the Sydney performances of HEARD, the Chicago-based artist unveiled the first permutation of UNTIL at Mass MoCA. Like Cave’s first Soundsuits – the first of which was created in 1992; an armorial suit made of twigs in response to an act of racially-charged police brutality, the murder of Rodney King in Los Angeles – UNTIL addresses contemporary incidents of racial violence and police brutality: the tragic killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland and Trayvon Martin, amongst countless others. “UNTIL takes its title from the expression ‘Innocent until proven guilty, or guilty until proven innocent’”, Cave told me. “It’s a piece that’s really grounded in the political climate right now in the States around the endless unarmed black men that have been losing their lives.” Three years in the making, UNTIL matches ambition with scale, creating an immersive wonderland of found objects, tchotchkes, millions of beads and crystals; air, light, sound and movement – a multi-sensory feast, the beauty of which masks a grave and sobering undercurrent. UNTIL is, essentially, an invitation to step inside Cave’s largest, most visceral Soundsuit to date.

UNTIL began with a question as catalyst: ‘Is there racism in heaven?’ As to whether Cave can answer it, well, he’s not certain such an answer exists. “Because I’m not sure that’s what I believe – that there’s a heaven”, he said earlier this week at a preview of the work. “[It’s] a question that came about as I was working in the studio one day and the Michael Brown incident transpired… That thought, as I was working, ‘is racism in heaven?’ was so profound that it lead to this object above my head to be created.” That object is the Crystal Cloudscape, an astonishing sculptural installation composed of countless found objects, chandeliers and thousands of crystals all threaded and knitted together to form a 5.4 tonne mass that hovers at the centre of UNTIL like a spectre of dread and the sublime – its form and vastness giving weight to and doubling as a vessel for the questions that are central to Cave’s astonishing body of work. “These are the things that I need to become the activist that I am in terms of building these types of experiences,” Cave said. “Particularly within this time right now.” Atop the structure, which has been in the process of installation for a number of weeks from twelve separate parts each affixed to a hollow scaffold, is a microcosm of the world’s surplus in miniature: an absurd topography of objects sourced by Cave and his partner, the artist Bob Faust, from second-hand stores, antique and flea markets that spans an entire spectrum from the ridiculous to the grave. Their inclusion speaks to Cave’s interest in shifting the dialogue around objects in order for both artist and viewer to move forward. Crucial to this and stationed throughout are 17 cast iron ‘Jocko’ style lawn jockeys, whose features are those of a conventional racist caricature of the servile African American from the Jim Crow era of legislated segregation and whose mythology stems from the folklore of Jocko Graves – an African American boy who served with George Washington during the American Revolutionary War and who froze to death overnight keeping watch over the horses. In UNTIL, Cave reconfigures the collective experience of racist memorabilia, swapping their lanterns for dreamcatchers fashioned from vintage tennis racquets and bead-strung nets. They stretch skyward, featherweight with new life.

Before you can reach the Crystal Cloudscape, however, you are greeted at the threshold by another work, the Kinetic Spinner Forest. There is no interstitial space between the doors of the institution and the borders of the work (it’s here that the Sydney iteration differs significantly from its initial version in Massachusetts, where guests entered the work at the bottom of a staircase that afforded them time to sit and observe before being thrust into it – no such reprieve exists here). The Kinetic Spinner Forest consumes the entire entrance foyer at Carriageworks, a staggering void rendered dazzling through the suspension of 1,800 metallic spinning ornaments – not unlike those you will soon find hanging from Christmas trees – that on closer inspection reveal themselves to have taken the shapes of bullets, handguns and tear drops. Cave subverts the decorative object, interlacing hope and beauty within despair. Nearby, a 14 channel video work, Hy-Dyve, explores the states of anxiety and agitation fuelled by pervasive notions of surveillance and racial profiling. The work includes a stunning floor-mapped video projection that was shot locally in Sydney using a drone at Little Bay; an enormous lifeguard’s chair concealing the only Soundsuit in UNTIL atop which sits a minstrel figurine; and a second 360 degree projection on the walls which offers viewers their first glimpse of Cave in the flesh – only his eye visible through a Soundsuit with the head of a chicken that is cast in a maddening dance intercut with more racially-charged minstrelsy, connecting the work to the lawn jockey statuettes that figure so prominently in the canopy of the adjoining room.

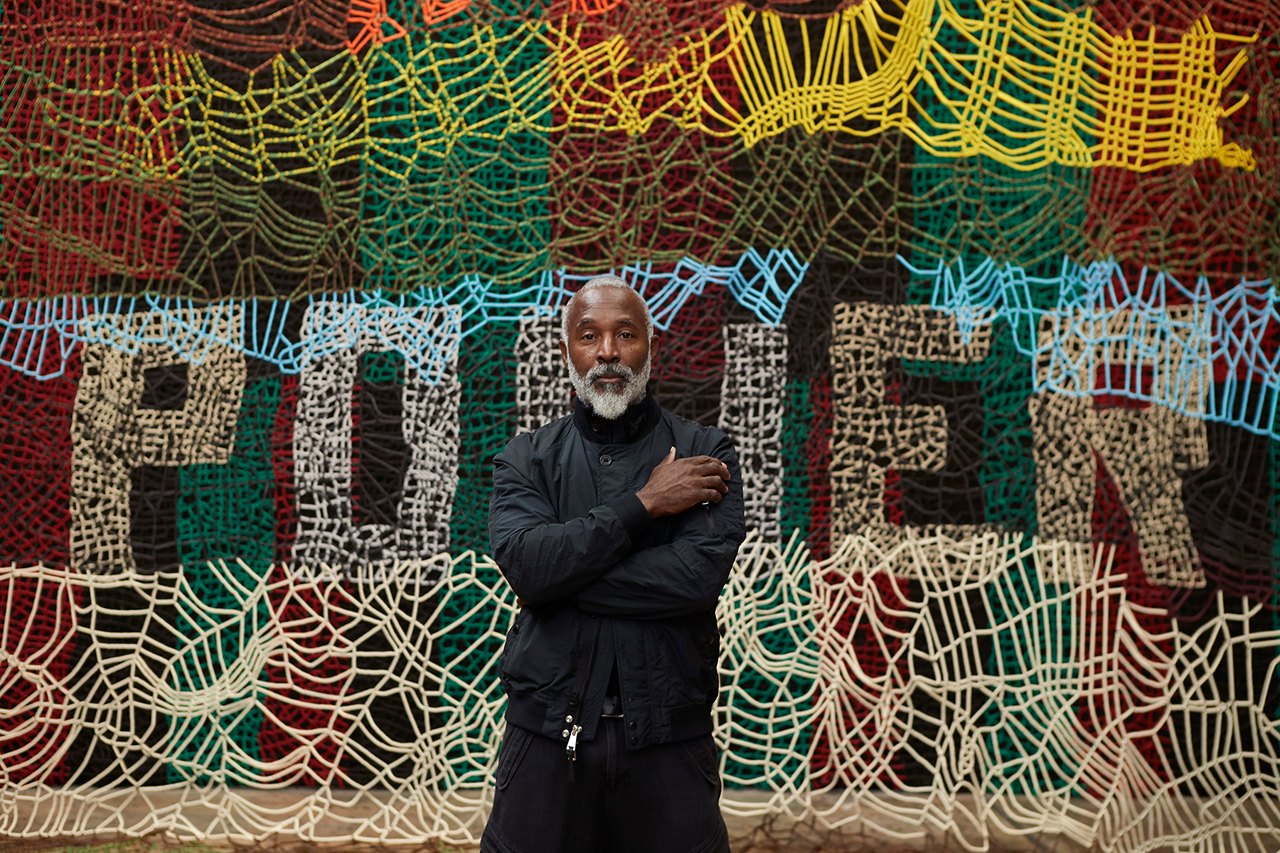

That Cave is capable of producing successive works that build cumulative awe is nothing short of astonishing. A final bay hosts two works, Beaded Cliff Wall and Flow/Blow. The latter is an installation that gives shape to the cleansing, life-giving and sustaining properties of water and oxygen writ large in an sculptural form comprised of metallic party streamers set flying by 14 industrial fans. It will also prove, no doubt, to be summer Instagram bait nonpareil. Beaded Cliff Wall, then, is an installation comprised of ten handmade curtains woven from millions of plastic hair pony beads by Cave and 12 assistants over the course of 18 months. Strung onto shoelaces and cargo netting, the cumulative effect is redolent of a sheer cliff face strewn with graffiti. When shown at Mass MoCA, Beaded Cliff Wall was presented as a topographical, sculptural landscape. Here, however, Cave has strung the nets from a great height, the works unfolding and pooling on the ground to create a formal cavity that engulfs their viewer and provides a forum for another key element of UNTIL.

“It really is about creating a platform for conversations to be held within this sort of performance installation, so there’s a lot of call and response,” Cave said of the body of work, which will invite groups of artists to create smaller performance works around issues of race and gun violence as part of a curated program of free events spanning music, theatre and performance, alongside panel discussions and community forums that echo Cave’s commitment to engaging the cities and communities where he stages his work. Contributors to the program include Romance Was Born’s designers Luke Sales and Anna Plunkett; the dancer and visual artist, Bhenji Ra; the chef, Kylie Kwong; visual artist Atong Atem and the singer-songwriter, Ngaiire, amongst others. “It’s also becomes a convening space for civic leaders to come with community leaders and talk about issues that are really separating and destroying the infrastructure of our communities,” Cave added.

UNTIL will be presented free to the public over a six-month period at Carriageworks. I asked Cave whether he thinks the work will carry with it the same resonance that it has had in the States – arguably the nexus of gun violence, race and the resulting deaths in police custody – and he pauses for a moment before responding, “It will have the same significance. I don’t think it will be about gun violence here but it will be about other issues that are, let’s say, dealing with ‘isms’ [racism, sexism, colonialism, et cetera] within your own communities and world.”

“I’m a messenger first and artist second”, Cave added during the preview of the works. “That liberates me from my responsibility. Being an artist is a lot of responsibility. Being a messenger is not. And so it’s these kind of environments, these dream spaces, that I create with the intent that they will be used and become platforms for other artists, individuals and communities to talk about the ‘isms’ that we all deal with in our daily lives. Yes, this is a work of art, but it also knows how to set itself back in order for call-and-response to happen. That’s something that I’ve always done – it’s my sort of outreach, my way of being proactive and using art as a vehicle for change.”

Almost hidden amidst the enormity of scale, form, light and movement of UNTIL is a separate work from 2016, Unarmed, which presides over the spectacle with a quiet grace. Taking the form of a small shrine at the centre of which is a bronze cast of the artist’s hand posed as though it were pointing skyward, Unarmed also features a frame in the form of a laurel of intricate, beaded flowers. It is set against Wallwork, a kaleidoscopic backdrop created by Bob Faust, an abstract extrapolation of a Soundsuit exploded beyond recognition. Tilt your head to the side and you’ll see that Cave’s hand has also assumed the position of one’s hand were it to hold a handgun, finger resting gingerly on the trigger. It is, Cave says, his way of paying “homage to those individuals [who have died] and choosing to use my body as a way of expressing my grief, pain and sorrow… It’s everything that I am struggling with. It’s everything that I need to carry on.”

Nick Cave: UNTIL will exhibit at Carriageworks from November 23 until March 3, 2019. More information is available here.

Tile and cover image: Courtesy of the artist/Zan Wimberley