News feed

Timely. It’s the buzzword surrounding almost every international review of Steven Spielberg’s high-wire newspaper drama The Post. And in the modern day, as the free press and the truth is challenged and assaulted by White House terms such as “fake news” and “alternative facts”, the lauded director – along with Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks – tell the true tale of the great battle between the freedom of the media and government security. Before Trump, before the internet, before Watergate, there were The Pentagon Papers; the big lies told by four presidents to the American people – and thus the world – surrounding the allies’ progress being made in the Vietnam War.

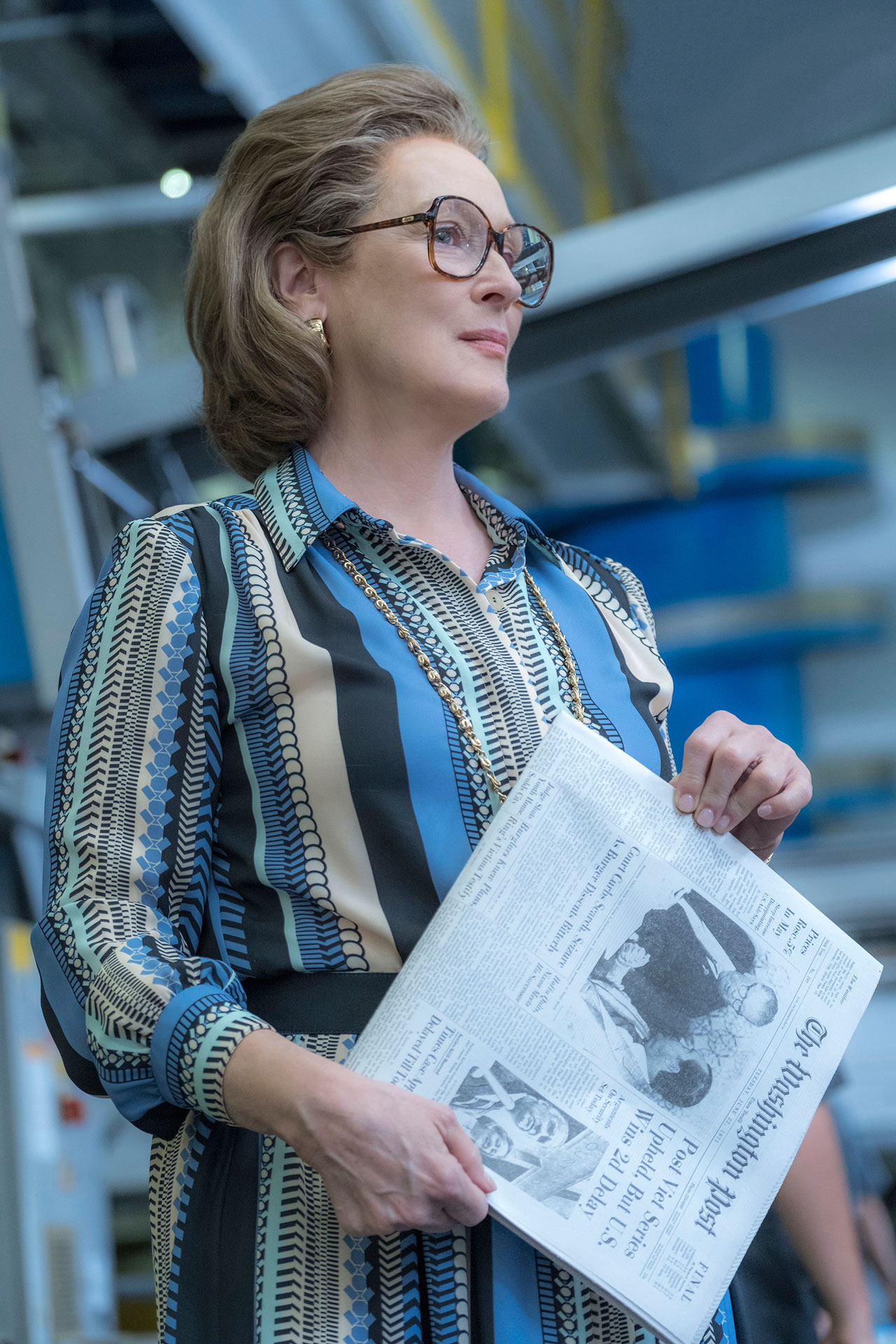

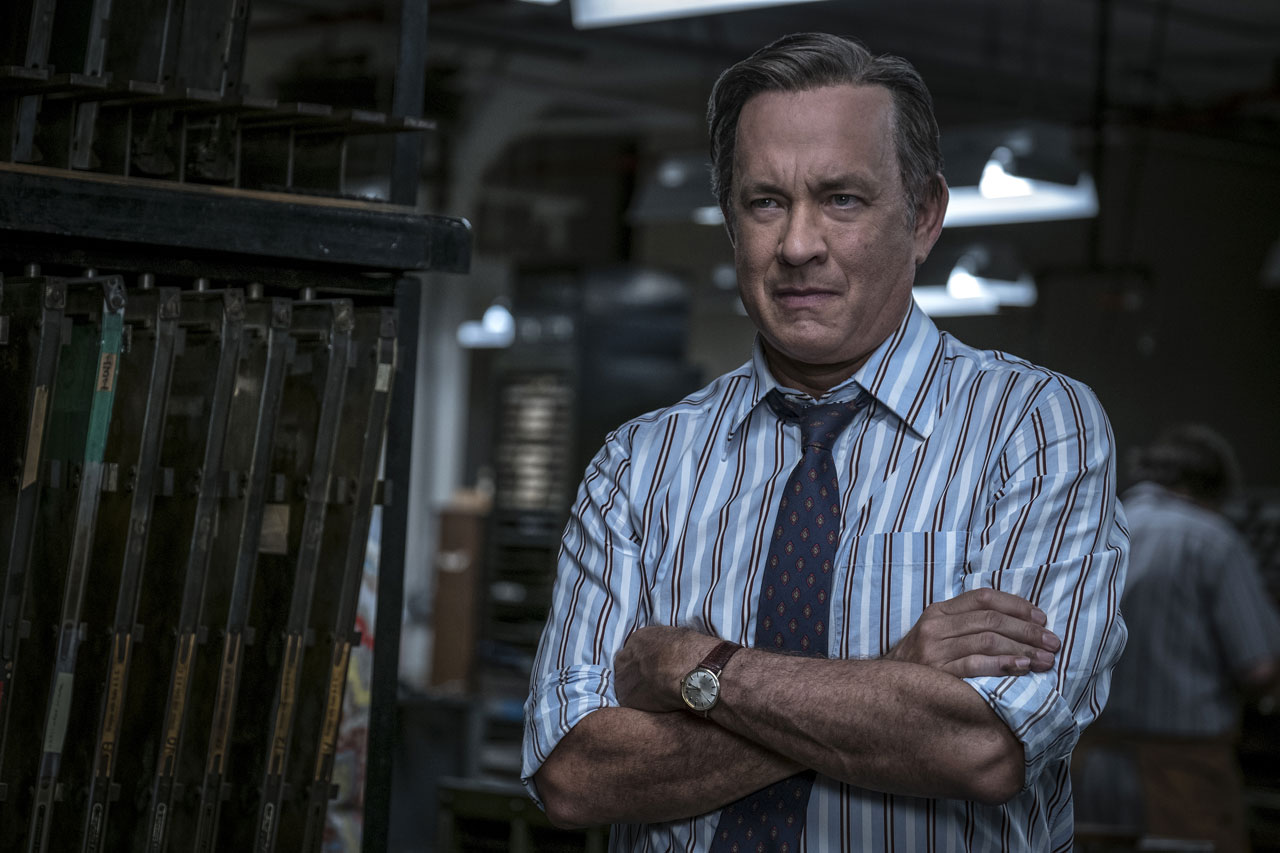

The year is 1971 and in a time where women were homemakers and retreated to the sitting room after dinner while their husbands spoke about business, politics and world issues over whiskeys on ice, Streep plays Katharine Graham, the first female publisher of little local newspaper The Washington Post. When rival national giant The New York Times receives an injunction order from the Nixon government to stop running a series of excerpts of the Pentagon Papers (which say the U.S. administration knew the war couldn’t be won but kept sending battalions of men into battle for five extra years to avoid the humiliation of an American defeat), pressure is on The Post’s journalists to swoop. With relentless editor Ben Bradlee (Hanks) at the publication’s helm, he steers Katharine into a decision: ignore the injunction, risk imprisonment and the closure of the paper by printing the government cover-up and potentially save thousands of military lives or…remain quiet.

Working in Ben’s living room – while his daughter makes lemonade and his wife Tony (Sarah Paulson) serves sandwiches – five journalists work overtime to read and interpret 4000 pages of reports from Vietnam’s frontline. The pages are unnumbered, mixed-up and while The Times had three months to work on the original investigation, The Post have just ten-hours before the print deadline (and with no real clue on whether a nervous and inexperienced Katharine will actually push publish). There are no emails; Couriers by way of a small boy running swiftly between sources and offices deliver top-secret hard-copy files. There are no computers; And golf ball typewriters mean one mistake green lights starting-over. There are no USBs or server filing systems; piles and piles of papers sit on every desk. Conference calls mean different rotary telephones are picked up in different rooms of a house or office. Sub editors edit with a pencil. Yes, while today’s press work quickly in a world where communication is instantaneous, we come to appreciate just how hard and fast news journalists worked pre-internet.

When we first meet Katharine, sunlight beams into her office. Her hair is perfectly set, her pussy bow blouse perfectly pressed. The Washington Post is barely solvent after she was unexpectedly left the title after her late husband committed suicide. It is Katharine who must face an all-male boardroom – where she is spoken over the top of – to convince financiers The Post is worth investment. There’s an interesting dynamic, too, between Ben and Katharine. It’s respectful (she is Ben’s boss) and she trusts him implicitly but when it comes to daily decisions, Ben has Katharine where he wants her; gender inequality trumps rank.

The film is as much about Katharine staking her ground as a woman in a shifting world as it is about journalistic independence and governmental accountability. We must marvel at how, 47 years later, we are still grappling to set these notions straight.

In the first film where the credits include both Hanks and Streep, the pace is intense and the ride thrilling. Must-watch.

The Post is in Australian cinemas now.