News feed

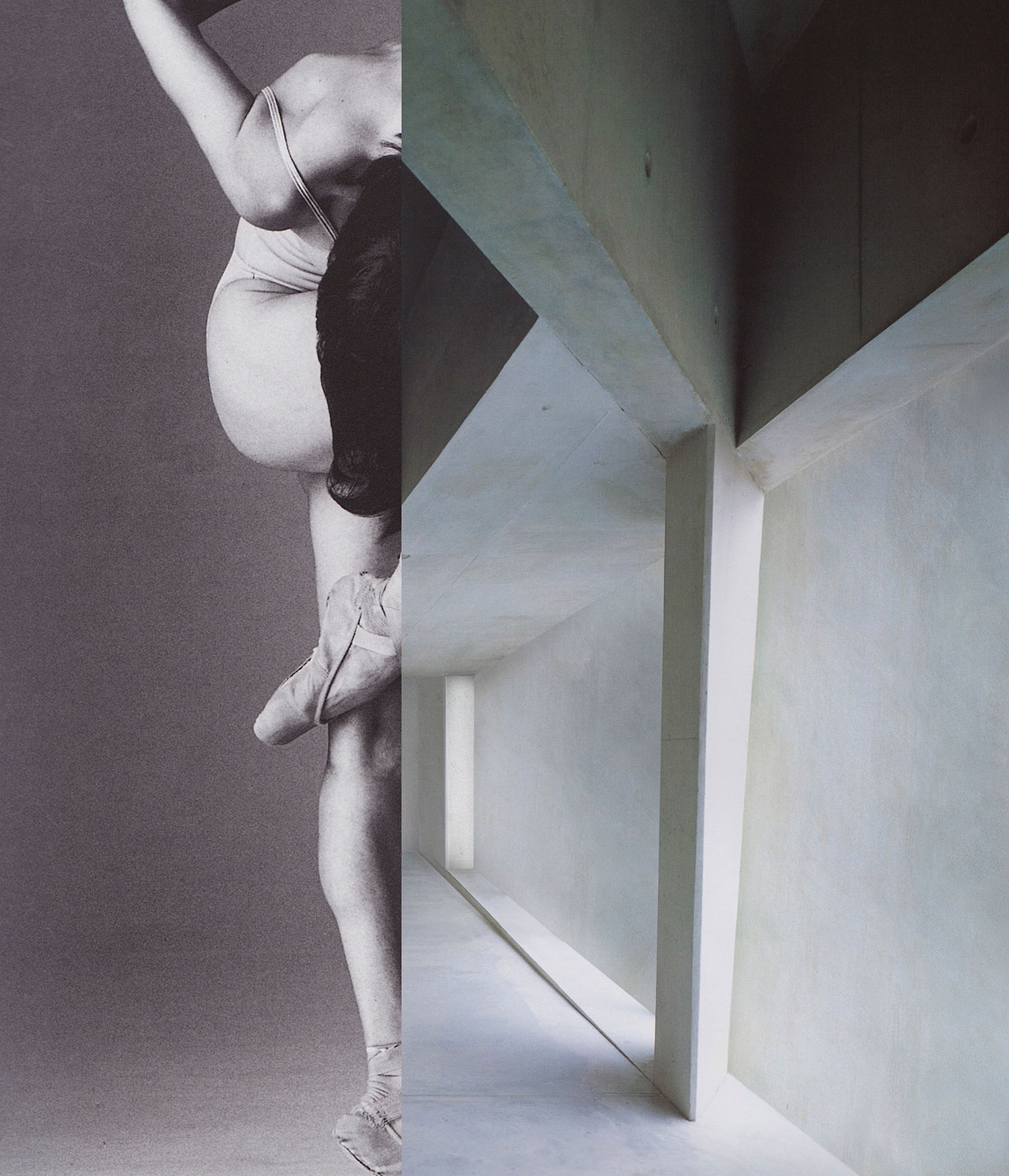

Zoë Croggon, Bow 2013, Collection of the artist

Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Daine Singer, Melbourne © Zoë Croggon

Five years ago, in a moment of quietude the likes of which only working in a bookshop allows for, Zoë Croggon was struck with a realization – the kind enjoyed by many, if not most, experiencing their first year out of art school.

“’Jesus, what have I done?’” she recalls thinking despairingly. “’The only thing I can do is put two pieces of paper together and, perhaps, create a synergy.’”

It’s as crude a summary of Croggon’s work as you could imagine, and though it comes courtesy of the artist herself, it ignores many of the complexities that make her collaged photo works the utterly arresting visual studies that they are – the kind of breathtaking pieces worthy of a solo show in a national gallery at the age of 27.

For someone whose work suggests a lifelong affinity for both surgical precision and the obsessive stockpiling of images, it’s something of a happy accident that Croggon fell into photo-collage. That she should become an artist, however, feels as close to predestined as reality will permit.

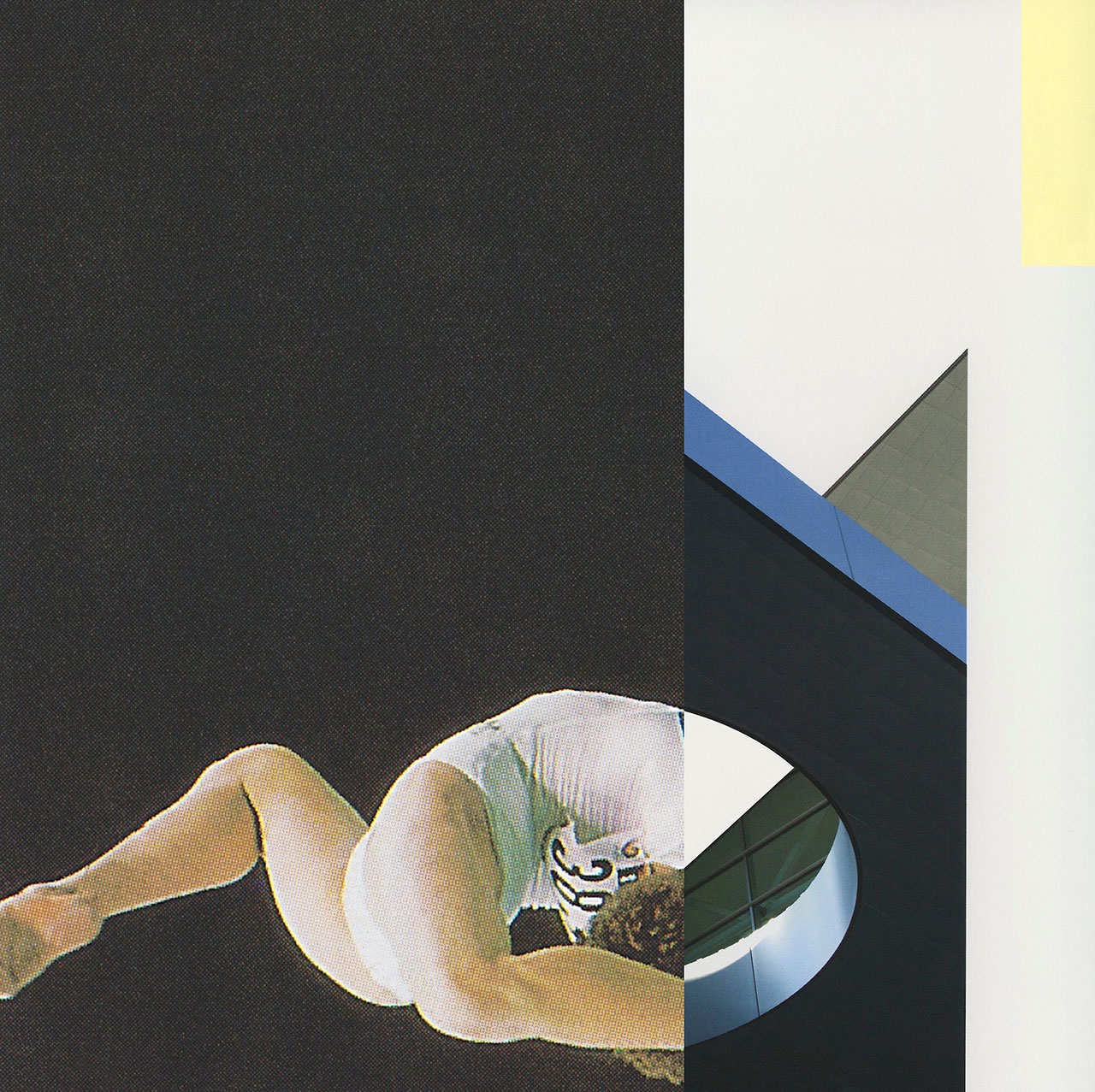

Zoë Croggon, Gymnast #1 2013, Collection of the artist

Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Daine Singer, Melbourne © Zoë Croggon

The second of three children born to two writers in the western suburbs of Melbourne, Croggon’s immersion in a rich cultural context began at an early age. In lieu of employing a babysitter, Croggon’s mother, a theatre critic, would arrange for her to attend readings and performances that cultivated an early fascination with the theatre in its manifold forms. But it was dance, ballet in particular, that would prove the most beguiling of these close encounters – providing an introduction to a discipline that she would go on to study for several years.

“It was this sensation of the kinetic body that I was so drawn to. Any way of plotting that was really fascinating to me.”

The fascination with dance soon faded from focus and Croggon “stopped thinking about it at all”. Prior to studying a Bachelor of Fine Arts at the Victorian College of Arts, she says she abandoned dance as her interests guided her toward the formal study of drawing and art making. It wasn’t long, however, before dance “came so sharply back into focus” and her fascination with the practice was reignited, thanks in no small part to the proximity of the Chunky Move Dance Company to her college. She is still studying ballet to this day.

“My love of that movement, but also the way it can repurpose, reshape, reformat the body; what it means and how many different forms it can have,” Croggon says while accounting for her love of the art form. “It was only within that year that I started focusing on collage, and the body in collage. It happened quite cleanly.”

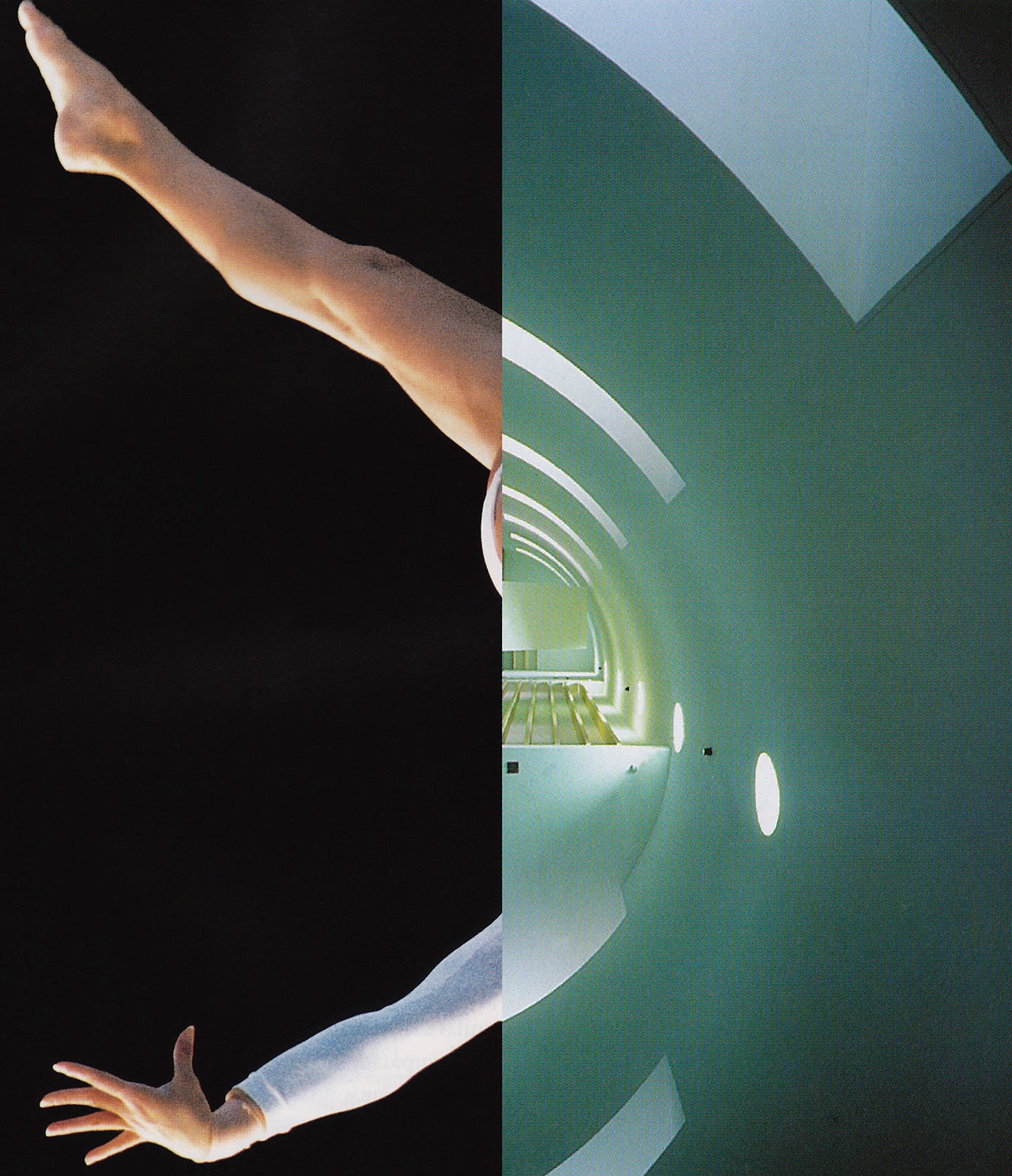

Zoë Croggon, Untitled #1 2015, Collection of the artist

Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Daine Singer, Melbourne © Zoë Croggon

But Croggon’s practice hasn’t always been so clean. At first, she dabbled in a mélange of “cut, paste, scissors, glue stick, all of that. Hundreds of things really intricately cut and formed” into a kind of barely controlled chaos that has ostensibly been eradicated from her work today. After her earliest formal experiments, a challenge then presented itself to Croggon: to distil the essence of the collage down to just two images, buoyed by the question of how much she could change the way a body looks by concealing it with another image.

The images themselves are primarily found photographs often drawn by chance from the printed materials of a bygone era. They are then scanned, printed, folded or sometimes cut into Croggon’s deft and disparate compositions. Her practice oscillates between the analogue and digital worlds, though she struggles to articulate even to herself a reason as to why she won’t source images online, besides the physical limitations that a book imposes in a world that resembles one large interminable assemblage.

If that is one of two dialectics in Croggon’s work, then the other is an interrogation of the relationship and tension between the kinetic body and its stationary counterpart in the built environment. In Croggon’s hybrid compositions, the line of the classically trained body of a dancer or athlete in motion segues effortlessly into the curvilinear and geometric shapes of modern architecture, think an Olympic gymnast eerily coalesced into Oscar Niemeyer’s modernist Niterói Contemporary Art Museum; their seemingly antithetical parts are conflated through a mutual sense of form and discipline that Croggon herself also shares in.

Zoë Croggon, Gymnast #1 2013, Collection of the artist

Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Daine Singer, Melbourne © Zoë Croggon

As part of Tenebrae, her biggest solo show to date at the National Gallery of Victoria’s inaugural Festival of Photography, Croggon will for the first time create an immersive five-screen video collage that dissects found footage drawn from the National Film and Sound Archive and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. It too will take “the body and its representation in cinema” as its subject in “a direct aesthetic relationship with the collages” that will appear alongside it, including a series of 10 handmade works created last year and inspired in part by the life and work of the late Japanese author Yukio Mishima and his relationship with his body and photography.

At times, Croggon’s minimalist abstractions in film and photography exude an ease that belies the rigours of her exhaustive and compulsive process of sourcing, documenting and compiling images. At others, Croggon wants you to see the interruption that her hand has caused as the embodiment of a division between reality and representation, “especially in relationship to photography as a medium.”

It is the mark of often months of agonising work, some of it tedious, all of it exacting and aiming always for that moment of synergy – the kind that at first seemed inconsequential to a then-23-year-old intent only on keeping intact all the pages of a bookshop in which she worked (and still does to this day).

“When it happens, when you realise that these two images have a dialogue, it’s kind of euphoric. Sometimes I have this perspective where I zoom out and I watch myself in my studio and think, ‘Jesus Christ, I feel insane.’ There are piles of books and photocopies everywhere and I’m sitting here curled up in a ball, trying to make things look good together.”

Zoë Croggon: Tenebrae is exhibiting as part of the Festival of Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria, March 17 – July 30. You can find out more information here.

Tile and cover image: Zoë Croggon, Fonteyn 2012, digital type C print, 102.8 x 99.9 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © Zoë Croggon