News feed

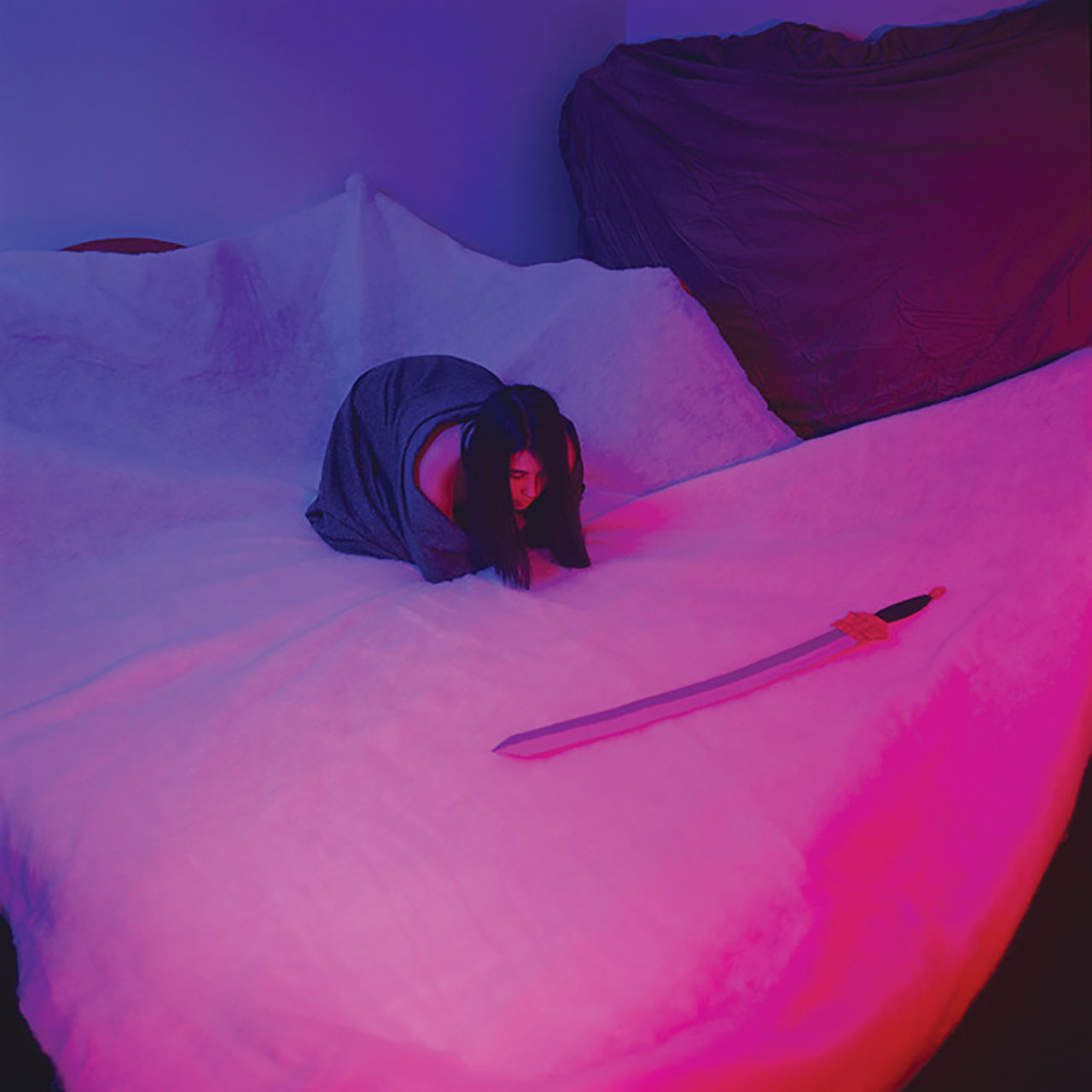

Boys will gladly go to war for you, 2014, C-type Photograph, 76.2 x 76.2cm

Credit: Courtesy of the artist

Zoe Wong was a child in Wollongong when she first saw Mulan with a school group. Mulan, she says, was the first cartoon character she saw that resembled her, and so she absorbed the contents of the film as though it were knowledge of authentic Chinese culture and not the hegemonic product of multi-billion dollar diversified Western media empire. “I never grew up with a lot of exposure to Chinese culture and so any media that contained Chinese characters or settings, I was really drawn to and looked towards as a guide for how to view or contextualise myself within that culture,” says Wong. “The ironic part is that Mulan was not even produced by Chinese people nor did it really have any correct Chinese customs or attitudes. And so I became really interested in this complexity behind misrepresentation and how it affects our perception of race and culture.”

In June, Wong was awarded a prize for her contribution to the Emerging Artist Exhibition at The Galeries, a body of work titled You’re a good Chinese girl. It was an experience she says helped to solidify her art practice. The exacting self-portraits that comprise it are both formal and theatrical, drawing heavily on scenes recreated from that formative exposure to Disney’s Mulan to interrogate how identity often forms in liminal spaces between the binaries to which we’re assigned from an early age: “East/West; Male/Female; Asian/Caucasian”. Wong created the sets, props and costumes in the lounge room of her apartment by hand using hand-painted paper and cardboard, arranged the lighting and performed the roles of both model and photographer using her camera – a Hasselblad and 120mm film – to decide on the format which the final images took, with little variance between takes thanks to meticulous pre-planning and the constraints of her medium.

The final set of photographs sees Wong return to a place in her childhood. To complete the work, Wong says she re-watched the film several times – an experience she says both invoked memories of viewing it as a child and required that she adopt a more critical scope to assess the film’s comparatively myopic representation of Chinese culture. “I’m very much interrogating a desire within myself for more of my Chinese heritage, or wanting to be more Chinese and so imitating and appropriating screenshots from the film became the basis of the work.” Wong says she began appearing in her own work as a way of interrogating her own heritage as well as issues around racial identity, with the medium of photography presenting her with the best format for doing so on enrolling in a degree in photography at the University of Technology Sydney. “I love using photography because of its dichotomy between what is true and what is false. It can also be evidence of a memory or event. I like how the medium parallels the concept, in that the work is always flipping between what we perceive as true or false.”

It was good when you were here, 2016, C-type Photograph

Credit: Courtesy of the artist

In this as in other works, Wong plays the central character. Another series, Uncle Jackie, sees her stage moving, quotidian scenes that are suddenly made absurd by the presence of a life-size cut out of the actor Jackie Chan. In another, Untitled (Communist Posters) Wong excises the faces – many of them Mao’s – from the titular propaganda posters and replaces them with her own, her features exaggerated and outlined in cartoonish black paint. All three see Wong place herself at the centre of a dialogue from which she has been excluded by virtue of time and place, history and tradition, and the binaries she dismantles in her work.

“I guess if someone were to ask me what I was, I would say ‘Australian’ but that in itself (as an identity) is loaded and complex,” says Wong, who says she was raised by parents who surrounded her with both the work of their artist friends, her mother’s own ceramics, and works exhibited in galleries from an early age. “Sometimes I stubbornly reply with only ‘Australian’ because I know the only reason people ask me ‘What are you?’ or ‘Where are you from?’ is because I’m not fully white and therefore surely cannot be ‘Australian’ (insert eye roll here).

“I grew up in Wollongong, which has always been quite a mixed community and so I never felt out of place. It was only when travelling to Albury or more rural towns to visit my family or going to China and Hong Kong that my differences became super apparent to me. I’m very fortunate to have never experienced violent or high levels of racism, just the occasional ‘What are you?’ and ‘Go back to your own country’, which of course fell on deaf ears. But certainly there has always been an experience of what I have termed ‘double othering’ in which you are ‘othered’ for not being fully ‘Australian’ and yet when in an Asian context, I am not fully Chinese either so am ‘othered’ again. It’s a very in-between space to occupy.”

Poster 2, 2013, Inkjet Print, 81 x 56cm

Credit: Courtesy of the artist

Wong does not appear in all of her works, however. In Lez We Forget, the artist once more appropriates the iconography of popular culture to address one of its most nefarious tropes: ‘bury your gays’ and its more specific sub-genus, ‘dead lesbian syndrome’, which is the shared tendency in works of fiction to deny LGBTQIA+ characters a conventionally happy ending, largely through untimely and often unjust or graphic deaths. The work itself is a series of shrines laden with tributes to fallen queer and lesbian characters, including Orange Is The New Black’s Poussey Washington, The L Word’s Dana Fairbanks and Xena Warrior Princess, each character’s date of death inscribed on a crucifix or plinth. Like her other pieces, it’s both poignant and pointed; there is a palpable sense of humour that is counterbalanced by a feeling of loss. “Lez We Forget was intended to acknowledge and point out something I felt may have been neglected and overlooked within pop culture,” says Wong, “But also to create a physical space of mourning for these fictional characters whose onscreen representation have impacted me and undoubtedly many others.

“I’ve always been interested in how popular culture as a reflection of society, whilst simultaneously, it also informs society and behaviour towards one another. I like to poke holes in this, look at where representation might be lacking or incorrect and how this affects particular communities. Growing up, TV and cinema always had a huge influence on me, and certainly when I was coming to terms with my own sexuality, seeing lesbian characters on screen helped validate what I was going through, and informed the way I looked at myself. The flip side of this, of course, is that queer representation onscreen isn’t amazing, and so this work was about creating visibility for this problem and also depicting a representation that I felt was needed to counter this issue.”

At left, I will never pass for a perfect bride or a perfect daughter; and right, A pendant for balance, both 2014, C-type Photograph, 76.2 x 76.2cm

Credit: Courtesy of the artist

I should never have left home, 2014, C-type Photograph, 76.2 x 76.2cm

Credit: Courtesy of the artist

In You’re a good Chinese girl, Wong hopes to offer audiences an insight into an experience that is solely her own, and if shared similarities emerge between the work and its viewer then “that makes me beyond happy!

“My works always has strong personal storylines and influences behind them. When dealing with the representation of race and sexuality I’m always very conscious of not speaking for others. I’m not trying to say, for instance that my experience and my work is representative of all half Australian, half Chinese people, or even inform people who are unaware of these issues of representation. Above anything else it’s about generating content that is self -representative, that acknowledges the flaws in representation around us and cuts into that by standing on its own.”

Tile and cover image: Courtesy of the artist